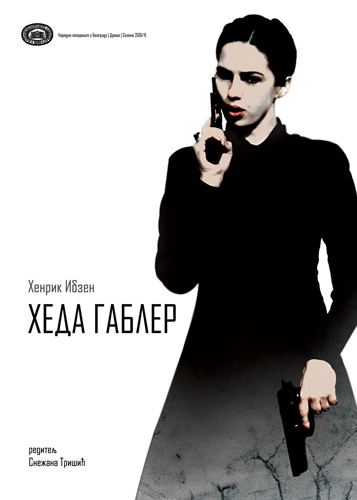

Hedda Gabler

drama by Henrik Ibsen

IBSEN, A POET OF INDIVIDUALISM

First productions of most Ibsen’s works have exceeded the scope of theatrical events and caused fired discussions and harsh social disputes. Atmosphere of polemics and importance of Ibsen’s work for his contemporaries is best seen in the fact that historians often treated the dramas as events equal to real ones, as historic facts that influenced forming of a modern state of mind. Intensive discussions about Nora Helmer leaving the “doll’s house” are still basis of each debate about gender equality. Moreover, Hedda Gabler does not cease to incite opinions, as intensively today as in the time of the first production. As opposed to Nora, Hedda never had any supporters; to the contrary, she always caused abhorrence. Similar to Antigone, Nora was a “saint of culture”, she still belongs to civilized, although personally dangerous system of values. Hedda steps over the line. Similar to Medea’s tragedy, her tragedy threatens to jeopardize our culture. Her tragedy does not deserve awe with contemporaries. Like Medea, Hedda was not “a saint”, she was a threat for culture. She does not deserve form of approval – she is regarded as a cruel, untamed, intolerant person. A critic even called Hedda “a monster” and “a miscarriage” of Ibsen’s imagination, in addition he thought that “Ibsen’s modern drama is a drama of abnormality” and that “his leading characters have nothing humane in them, except for human bodies they are wearing”. Even Georg Brandes, one of leading critics of Ibsen’s work, placed Hedda’s case into the field of pathology. As a particular case, she fits neither into the concept of individualism nor into a concept of literary character of the time. However, Brandes’ assessment has been contended by vitality of the character: even a hundred and twenty years after its appearance, Hedda Gabler manages to provoke full intellectual and emotional involvement of a viewer – as if it has just been written! Who is Hedda Gabler? Where does her arrogance come from? With what right does she demand everything from others while, at the same time, she is not capable to provide even simple kindness herself? These are the questions actors struggle with while working of this Ibsen’s piece, commonly known as “A Female Hamlet”. Hedda Gabler was a logical consequence of Ibsen’s radical individualism. Ibsen’s biographer Ivo de Figueiredo claims that Ibsen’s individualism represents a consequence of a longer process during the nineteenth century that evolved in “a series of touches” – from a teacher to a student; and “a touch” between Kierkegaard and Ibsen represents a culmination. The change, also known as “a gigantic transformation of western mentality”, was ready to happen long before Ibsen. In the 60s, the liberalism and faith into individuum reached its peak. All basic values were challenged: freedom and society, faith and knowledge, ideas and reality, individualism and world. The spirit of the time showed resistance to tradition, authority and institutions, conflict between science and faith, ethic individualism, psychology “searching the soul”, interest for imagination and folly… Individuum was placed in the centre, with this came a terrible burden to solve all life mysteries on one’s own, even if it meant negation of God. Ibsen is a great poet of this historic change. For him, writing was always “a battlefield” and the purpose – to remap the society. Leading role should be given to an individual – to aristocracy of his character, consciousness and will. Ibsen leaves behind the “holy collectivism” and romanticism – and turns to “holy individualism” (Gudliev Bø). Starting from Peer Gynt, who “gloats because of the strength of his I” and Brant “the new man” of modern Europe (liberated from the burden of tradition and institutions, but still symbolically representing collectiveness), through lonely fighters for “ethic individualism”, like Doctor Stockmann and Nora, Ibsen has inevitably evolved towards Hedda Gabler. To Hedda, who represents – herself. In other words – an invisible entity that will be named a hundred years later – a female identity. At the margin of his manuscript, Ibsen wrote a short comment on Hedda, “She was murdered by conventions and etiquette”. According to feminist culture studies, we know which conventions and etiquette – those of which division into public and private is “founding moment of modern patriarchate” (Judith Butler). Ibsen is a first writer who placed a woman as an individual (and not a representative of universal humanity) into the focus of dramatic interest. As a great supporter of individualism, in Hedda Gabler, he anticipates the issue of justification to keep the universality of the category “individual” based only on male model. In one of his final plays, he asks the question of “ethics in individualism”. Everything Hedda wants is a personal, existential feeling of purpose, “an act of bravery” which “radiates beauty”. However, the suicide brings Hedda to the stage – from privacy into the public.

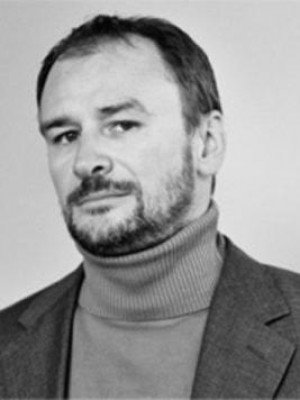

Slavko Milanović

HENRIK IBSEN

HENRIK IBSEN

There is a rule that at any given time there is a Shakespeare’s piece under production or on repertoires somewhere in the world. There are reliable indicators that Ibsen’s plays come right after Shakespeare’s. At the moment – according to information found at ibsen.net – there are 94 productions running, starting from Ibsen’s native town Skien to San Diego USA, and from Reykjavik to Teheran… Debates on Ibsen, his work and problems his pieces open, have been going on for a hundred and fifty years; they started as soon as the pieces were written. In order to illustrate the polemical atmosphere Ibsen’s premieres cause, Ljubiša Rajić gives example of Nora, “At the time when heated debates about the drama were in full swing, invitations for parties in Copenhagen stated that the guests were kindly asked not to discuss the drama during the parties.” Today, there are no parties where people get into intense discussions about art, but there are many Internet portals where discussions on Ibsen never stop. Literature on Ibsen is so abundant that it alone can fill a number of libraries and it becomes richer for dozen of new texts every day; this makes follow up on literature on Ibsen an almost impossible mission. In order to keep as much insight as possible, Ibsen Annual Journal publishes surveys of theoretical and critical reviews. And then, there are surveys of surveys… “A mortal man can”, Rajić says, “when it comes to time and language possibilities, find only a small portion of that abundance of literature available”. Encyclopaedia Britannica gives the following summary: „ Henrik Johan Ibsen born March 20, 1828 in Skien, Norway, died May 23, 1906, Kristiania (now Oslo), a major Norwegian playwright of the late 19th century. Ibsen was in the forefront of those early modern authors whom one could refer to as the great disturbers; he belongs with Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Friedrich Nietzsche, and William Blake. Ibsen wrote plays about mostly prosaic and commonplace persons; but from them he elicited insights of devastating directness, great subtlety, and occasional flashes of rare beauty. His plots are not cleverly contrived games but deliberate acts of cognition, in which persons are stripped of their accumulated disguises and forced to acknowledge their true selves, for better or worse. Thus, he made his audiences re-examine with painful earnestness the moral foundation of their being. During the last half of the 19th century he turned the European stage back from what it had become – a plaything and a distraction for the bored – to make it what it had been long ago among the ancient Greeks, an instrument for passing doom-judgment on the soul.“ Mayor plays: Brand (1866), Peer Gynt (1867), Pillars of Society (1877), A Doll’s House (better known under Nora – 1879), Ghosts (1881), An Enemy of the People (1882), The Wild Duck (1884), Rosmersholm (1886), Hedda Gabler (1890), John Gabriel Borkman (1896), When We Dead Awaken (1899).

SNEŽANA TRIŠIĆ

SNEŽANA TRIŠIĆ

She graduated from the Theatre and Radio Directing Department at the Faculty of Drama Arts in Belgrade, in the class of professors Nikola Jevtić and Alisa Stojanović (in 2009). As best in class of her generation, she won the “Hugo Klein” award. While still a student, she assists renowned directors Lary Zappia (The Sickness of the M Family; Yugoslav Drama Theatre) and Dušan Jovanović (My Family’s Role in the World Revolution; Atelier 212). As soon as in 2007, she independently directs (Brain Aphrodisiac, Dadov Theatre) and continues with Family Stories by B. Srbljanović (FDA – the production competed at the International Festival of Theatre Schools Setkani / Encounter 2008 in Brno, Czech Republic; Snežana received the Best Director Award). She is one of directors at the production Zum profil (FIST production at FDA; the play was performed at numerous festivals: the FAKI Festival in Zagreb; Les Rencontres Theatrales de Lyon, France; at the MIST – Manchester International Student Theatre Festival, Manchester, Great Britain; and at the Sterija Pozorje for Young Artists). After having done dramatization and adaptation of Charles Bukowski’s short stories, she directed Bukowski at a Bar (Theatre Left; the play participated at FAPS XII – Festival of Student Theatres of Serbia, Novi Sad and received awards for best leading male role and best costume; International Multimedia Festival PATOSOFFIRANjE 05 in Smederevo; BAP – Festival of Belgrade Amateur Theatres and won awards for best supporting actress, best costume and best music; and Apostrophe Festival in Prague, Czech Republic). She also directed The Class by Matjaž Zupančič (National Theatre of Republika Srpska, Banja Luka). She directed the first production of Aleksandar Radivojević’s Samoudica (Atelier 212; she won “Ljubomir Muci Draškić” award) and directed public reading of Landslide by Dora Delbianco (National Theatre in Belgrade). For her graduation assignment, she chose The Manifesto by Biljana Srbljanović and she is the author and director of documentary radio drama Slap a Smile onto Your Face (FDU)

In 2010, she won Kennedy’s scholarship and participated at numerous workshops in Washington, New York and Chicago.

Premiere performance

Premiere, February 20, 2011 / Stage „Raša Plaović"

Translated by Olga Moskovljevic

Director Snežana Trišic

Dramaturge Slavko Milanovic

Set Designer Aleksandar Denic

Costume Designer Katarina Grcic Nikolic

Composer Anja Djordjevic

Speech Ljiljana Mrkic Popovic, Phd

Choreographer Tamara Antonijevic

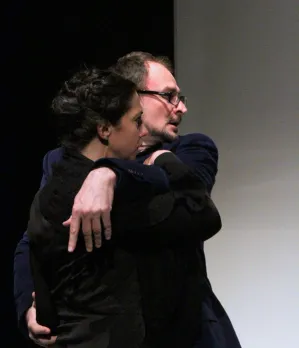

Premiere cast:

Jorgen Tesman, an Academic Aleksandar Djurica

Mrs. Hedda Tesman, Wife of Jorgen Nataša Ninkovic

Miss Julijana Tesman, Aunt of Jorgen Olga Odanovic

Mrs Elvsted Anastasia Mandic

Judge Brack Ljubomir Bandovic

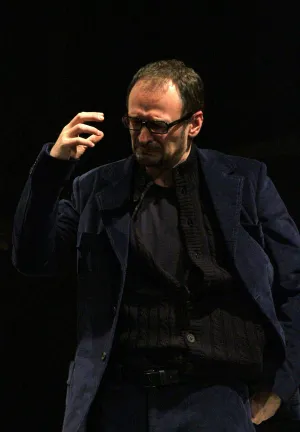

Ejlert Lovborg Nebojša Dugalic

Producer Jasmina Uroševic

Stage Manager Sandra Rokvic

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Assistant Director Nastasja Kastratovic

Assistant Set Designer Kaća Todorovic Krkovic

Assistant producer Jovana Cumic*

*student

Lighting Master Srdjan Micevic

Make-Up Artist Dragoljub Jeremic

Stage Master Nevenko Radinovic

Sound Master Nebojša Kostic

Set and costumes were manufactured in the workshops of the National Theatre in Belgrade