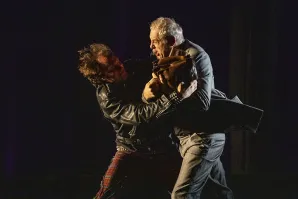

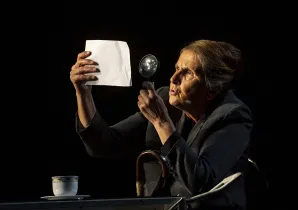

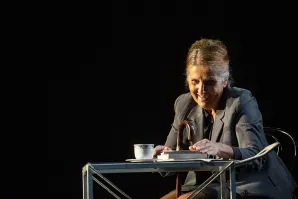

Wolves and sheep

comedy by Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky

.jpg)

A WORD FROM THE DIRECTOR

This is a masterpiece. This is a real treat for any director. It’s a classic, a discipline which has been neglected in our theatre. You rarely do Ostrovsky, but again, you also rarely do Shakespeare, Molière, Sophocles, Sterija...Why is that? Because it is quite demanding. It takes a lot of energy, talent, a star-studded cast. To create an artistic theatre based on the great works of classic literature represents a huge challenge for a director. Today, modern plays are done more which tell stories about everyday life and with particular focus on current political situation. And if they have neither a storyline nor characters, well, then it is a piece of cake to do them (laughter). Our theatre has less and less well-played classic pieces and the national theatre is obliged to produce the great playwrights and their masterpieces, as much we can do and in whatever manner we can do it. We should not give up on that. Cheap thrills sneaked into our theatre and that is why it is important that we play the classics - those classics that show how much beauty, how much spirituality exists in books which, actually, nobody reads. I like comic theatre, I made such shows with great joy, and I will keep making them.

Whenever I read a classic play, I feel the joy of discovering those places that show the constancy of human nature. It is the energy that I will pass on my crew and that moment represents the beginning of a creative process. That process, if the theatre stands behind the director and the project, eventually results in beautiful plays. It is with great pleasure and huge success that I did two versions of “The Forest” – in the Yugoslav Drama Theatre and in the New Theatre in Budapest. I made two completely different shows. From this play I really expect much because every role and every situation was brilliantly written. Indeed, such quality puts a great obligation upon us who do the play. It takes a great deal of acting skill, a sense for diving into complex psychological situations and, certainly, it needs a joint play that is quite hard to achieve. I hope that we will pull it off.

Ostrovsky wrote plays about the life as it is. He also wrote melodramas – “The Storm”, “Without a Dowry”, “Talents and Admirers”…He looked at love from different angles. The lovers always suffered some ordeal, they were manipulated, robbed, disgraced, humiliated, but they would keep forgiving only to be abused again. Those are people – sheep, spellbound and blinded by love and filled with undying passion for surrendering and yielding to greed and lust of people – wolves. Wolves are the slaves of their own hunger that torments them and eats them up inside.

In time of great crisis the masks fall off and the true human face emerges. Ostrovsky concludes with great sarcasm that behind the masks of distinguished citizens there are, actually, beasts. That is why he named the play “Wolves and Sheep”…Since the dawn of time the human kind exists divided into old and young, men and women, believers and non-believers, rich and poor, literate and illiterate, mad and sane, rascals and noblemen…but, there is a division which is, perhaps, older and more important than all of the above. It is a division into wolves and sheep. This division knows no limits, it exists among friends and lovers alike, allies and clans, gangs, parties, this division knows neither race nor nation, historical periods or cultures, affiliation or bonds. It is a division of all divisions. It is eternal and indestructible and accompanies every human life. There is not a man who lived in this world without becoming either a wolf or a sheep, or sometimes a wolf, but more often a sheep.

Most of us are sheep, however, from time to time we put on a wolf’s skin when necessary. Most often in self-defence. Wolves, which are quite fewer, are mostly in sheep’s clothing, camouflaged. Only some of them, the most domineering ones, are conceited and boast with their fangs. They show their fangs to us – sheep every day. This would be my idea of this allegory about wolves and sheep. However, the paradox is that most of the time sheep are just content by being sheep and they do not resist the moment when they are being ripped apart by wolf’s fangs. That is something in human nature that cannot be changed.

It is quite unbelievable a fact how deeply rooted is the idea of exploitation, of use, of theft in family relations, love relationships and even in the most subtle business relations. It is fascinating. We believe that closeness that we achieve with our family, friends, or in marriage, is a guarantee of respect and love. It is interesting to see how Ostrovsky doubts this and proves quite the opposite in a funny, sarcastic and accurate manner. Hence, it is dog eats dog among those closest with each other. I find this paradox, this absurd quite inspirational in theatre and I will try to bring this to light – those concealed, secretive evil intentions that people who are closest with each other harbour against each other.

Extracts from the interview with director Egon Savin conducted by Mikojan Bezbradica

Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky is deemed by many to be the most remarkable realist playwright in the nineteenth century Russian drama. He was born in the part of Moscow known as Zamoskvoreche, a wealthy commercial district, home to many merchant families. To please his father, who was a successful lawyer, he enrolled at the Moscow University to study law. However, he left University during his second year and entered the civil service as a scribe of the Court of Conscience in Moscow. Plots of Ostrovsky’s plays were mainly situated at courts, taverns, Zamoskvoreche and theatres, places that formed his backgrounds and life experiences. Ostrovsky introduced into a Russian literature and theatre classes of tradesmen, merchants, nouveau riches, and high-ranking clerks. He wrote his first play Picture of Family Happiness in 1847, and soon after with his second play (Bankrupt, 1850) he built reputation as a firm critic of society. Bankrupt was banned from the production by imperial censure and its author was put under five-year police surveillance and was dismissed from the civil service. In spite of ban, the piece became well known owing to its public readings at Moscow clubs and literary salons. A famous Russian critic N. A. Dobrolyubov wrote a legendary review of it titled No ray of light penetrates the “realm of darkness”. Bankrupt was actually produced thirteen years later under the title It’s a Family Affair – We’ ll Settle It Ourselves – first in Saint Petersburg and soon after at Moscow Malyi Theatre, and gained enormous success.

Alexander Nikolayevich Ostrovsky is deemed by many to be the most remarkable realist playwright in the nineteenth century Russian drama. He was born in the part of Moscow known as Zamoskvoreche, a wealthy commercial district, home to many merchant families. To please his father, who was a successful lawyer, he enrolled at the Moscow University to study law. However, he left University during his second year and entered the civil service as a scribe of the Court of Conscience in Moscow. Plots of Ostrovsky’s plays were mainly situated at courts, taverns, Zamoskvoreche and theatres, places that formed his backgrounds and life experiences. Ostrovsky introduced into a Russian literature and theatre classes of tradesmen, merchants, nouveau riches, and high-ranking clerks. He wrote his first play Picture of Family Happiness in 1847, and soon after with his second play (Bankrupt, 1850) he built reputation as a firm critic of society. Bankrupt was banned from the production by imperial censure and its author was put under five-year police surveillance and was dismissed from the civil service. In spite of ban, the piece became well known owing to its public readings at Moscow clubs and literary salons. A famous Russian critic N. A. Dobrolyubov wrote a legendary review of it titled No ray of light penetrates the “realm of darkness”. Bankrupt was actually produced thirteen years later under the title It’s a Family Affair – We’ ll Settle It Ourselves – first in Saint Petersburg and soon after at Moscow Malyi Theatre, and gained enormous success.

None of great Russian authors more than Ostrovsky touched the Russian merchants, that homespun moneyed class, crude and coarse, grasping and mean, without the idealism of their educated neighbors in the cities or the homely charm of the peasants from whom they themselves sprang, yet gifted with a rough force and determination not often found among the cultivated aristocracy. This was the field that Ostrovsky made peculiarly his own.

Ostrovsky was a prolific writer. He wrote 47 plays. Although there is no Russian dramatist whose plays were not banned, no one of them had even 16 dramas forbidden, as in Ostrovsky’s case. Even his translation of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew was prohibited. (Besides Shakespeare he also translated Terence, Cervantes and Goldoni.)

Despite the permanent ban, Ostrovsky’s plays were the most performed at the time. He himself gained success during his lifetime. At the restored Maryinsky Theater in St. Petersburg, on the new painted ceiling, besides the portraits of Fonvizin and Gogol, there was a portrait of Ostrovsky, too. He received recognitions even from the most powerful ones – emperors Alexander I, Alexander II and Nicholas I. But he didn’t succeed to start his own school of acting where actors would train in new realistic approach to acting. Towards the end of his life he was appointed a director of repertoire i.e. an artistic director of the Moscow Imperial Theatres. He devoted himself to his duties with great enthusiasm and planned to undertake thorough theatre reforms, but it was too late for him - he passed away just a few months after taking up his appointment, in 1886.

His literary credits include: Picture of Family Happiness, Bankrupt or It’s a Family Affair – We’ll Settle It Ourselves, The Poor Bride, Don’t Put Yourself in Another Man’s Sledge, Poverty Is No Crime, A Protégée, A Profitable Post, Live Not As You Would Like To, Suffering from Other’s Sins, The Storm, Vassilisa Malentieva, Kozma Minin, The False Dmitriy, Vasily Shuisky, Crazy Money, The Passionate Heart, Guilty Without Guilt, Even a Wise Man Stumbles, Every Day Is Not a Holiday, The Forest, Without a Dowry. His fairy-tale Snow Maiden was adapted into a libretto for Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera.

EGON SAVIN

EGON SAVIN

Biography

Egon Savin is a Serbian and Yugoslav theatre director and a full professor at the Theatre Directing Department at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade.

He has directed over seventy various dramatic productions, from contemporary domestic playwrights whose works he directed in informal theatre companies to world classiscs, at the largest national theatres. He worked across former Yugoslavia: Belgrade, Zagreb, Novi Sad, Skopje, Sarajevo, Podgorica, Rijeka, Sombor, Kruševac, Zrenjanin...Egon Savin’s productions had guest performances all over the world: in New York, Chicago, Montreal, Toronto, Paris, Vienna, Nancy, Mülheim, Wiesbaden, Zurich, Tel Aviv, Warsaw, Prague, Budapest, Trieste...

He is a recepient, often multiple, of all the most significant theatre awards for his creative work: Sterija Award, “Bojan Stupica” Award, “Ardalion” Award, “Turkey” statuette, “Joakim Vujić” statuette, several directing awards at the International Theater Festival MESS in Sarajevo, the Montenegrin National Theatre Grand Prize, “Jovan Đorđević” Gold Medal, Best Director Award at the International Small Scene Theatre Festival – Rijeka, April Award of the City of Belgrade…

At the National Theatre in Belgrade Egon Savin directed the following plays: “Cyrano de Bergerac” by E. Rostand (1991), “Kir Janja (The Miser)” by J. Sterija Popović (1992), “The Upstart” by J. Sterija Popović (1998), “The Last Demon” by I. Singer (2000), “States of Shock” by Sam Shepard (2001), “Death and the Dervish” by M. Selimović (2008), “The Deceased” by B. Nušić (2009), “The Misanthrope” by J.B.P. Moliere (2012), “The Miracle in Shargan” by Lj. Simović (2015), “The Nineties” by G. Milenković (2018).

Premiere performance

Premiere: September 25th 2021

Main stage

Аdapted and directed by Egon Savin

Set Designer Egon Savin

Costume Designer Jelena Stokuća

Vocal Coach Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Music Selection Egon Savin

Drama Producer Jasmina Urošević

Stage Manager Sanja Ugrinić Mimica

Prompter Marija Nedeljkov/Danica Stevanović

Assistant Director Nastasja Alja Daničić

Assistant Set Designer Jasna Saramandić

Premiere Cast:

MEROPA MURZAVETSKAYA Olga Odanović

APPOLON MURZAVETSKY,nephew of Murzavetskaya Bojan Dimitrijević

GLAFIRA ALEXEEVNA,poor young woman, relative of Murzavetskaya Sonja Kolačarić

YEVLAMPIA KUPAVINA,rich young widow Anastasia Mandić

ANFISA TIKHONOVNA, her aunt Danijela Ugrenović

MIKHAIL LYNYAEV,squire of honor, rich nobleman Radoslav Milenković

VASILY BERKUTOV,neighbor of Kupavina Aleksandar Đurica

VUKOL CHUGUNOV,former member of the district court Nebojša Kundačina

KLAVDII GORETSKY,nephew of Chugunov Bojan Krivokapić

PAVLIN SAVELYCH Dimitrije Ilić

Light Operater Miodrag Milivojević

Make-up Marko Dukić

Stage Crew Chief Nevenko Radanović

Sound Operater Nebojša Kostić

Sets and costumes were manufactured in the National Theatre workshops