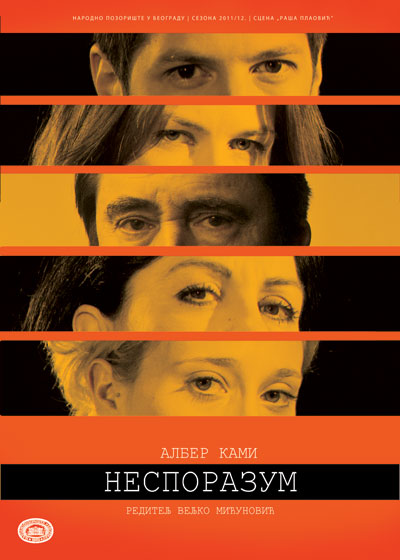

The misunderstanding

drama by Alber Camus

CREATION OF A SMALL UTOPIA AS A GOAL IN LIFE

Fictional dialogue between the director and dramaturge

Ž.H. The question from a more experienced and primarily well-intentioned colleague would be, ‘Why would anyone want to see a production of a philosophic drama nowadays?’ Especially, since we are all aware that the plot deals with a philosophical stand – which is a certain meeting point for all interpretations of the “genre” – as if provoking a debate regarding an opinion that a philosophical drama is not “suitable” to communicate with audience, since a dramatic appeal at present day has been equalled to the need to entertain the audience. Let us give a simple answer to the question why we are producing The Misunderstanding. Jan, the leading character of the Camus’ drama, has just turned thirty and he tries to define himself, only not through clear perspective of love in a family he is supposed to have with his devoted wife; instead, he tries to do that by going back to his long lost home, where he faces crime instead of motherly and sisterly love. The two of them justify their crime, which became the way and purpose of their lives, with the need to escape the grey reality and leave to a promised land about which they have no realistic information except for their suppositions that they would have better lives there. This piece almost glows with seductive appeal of Alberto Moravia’s thought which says that everyone imagines their heaven in the place where someone else’s hell is.

V.M. We presume that Camus wrote The Misunderstanding in the atmosphere of immediate despair right after the Second World War; the War marked the twentieth century in a dreadful and warning way. I perceive The Misunderstanding as a modern tragedy of search for happiness, faithfully following Camus’ dramaturgical context. Without a doubt, the context of this after-war trauma is present. The trauma continues and as it constantly renews itself here, as if it constantly and masochistically asks for fresh blood and pain. This is how the absurd of human existence in general, which Camus used to feed his works, carries on in our everyday lives, something specific of us, living, that we feel in our lives and clearly recognize in our fears and cynical denials and escapes from them…

Ž.H. The existentialism opposes secular morality that denied God for utilitarian reasons. History of liberal capitalism is a history of identifying God with ideology, which was intended to be replaced with another one, a better one and a more profitable one. It is not the freedom the existentialists dream of. Of course, it would be banal to think that Camus’ idea of freedom is incorporated in what his Caligula does. By interpreting existentialist’s idea of freedom as a principle that in the world we claim to be absurd each action is like that, even a murder, and allowed from this point of view, we dress the holly idea of Freedom into a coat of anarchism. On the other hand, anarchist were treated like Lenin treated Bacunin. Where is the actual freedom? Life allows everyone to find out on their own. As a rule, this notion comes in deathbed, when Devil closes the b&b where we have spent our lives.

V.M. Grotesque lack of communication between people and numbness seem to take place on a stage and it is almost banally realistic. This happens owing to the environment of monstrous lack of emotion and selfish greed, as well as in the atmosphere of obsessive focus on self and money. With this production, we ask the question why it happens. Is it hedonism, anarchism, miniature resistance in a time of recession of liberal capitalism… or simply an illusion of freedom, or cruel and immature execution of a dream about happiness? We wander what we are doing, where we are, where we are going to, how far… We wander why our God is in fact a poor person.

Ž.H. Philosophic dramas tend to be engaged. They may promote their philosophy, or policy. Existentialists do that with almost religious passion, regardless of means they use to persuade audience into their belief. Eric Bentley perhaps went the farthest while explaining this literary genre by comparing Sartre and Brecht and saying that both writers, in a historical absolute and in a conscious action to change the world, see the meaning of human existence, and try to establish synthesis of individual and social. “Europe is such a sad place”, says the wife of the leading character in The Misunderstanding. How can one say this and not be considered a Euro-sceptic?

V.M. We have put emphasis on that line. We consider it very important and contemporary. Is this place sadder than Europe which is a sad place? We wander this as well. Europe is a sad place or is it our dream about happiness? Maybe, America is our dream about happiness. On the other hand, maybe, Europe after all is our dream about happiness…

Ž.H. Renowned critics of Camus’ prose emphasise that one of his obsessive philosophical issues to which he tries to respond in his work is – how to respect a human life in the world void of transcendental meaning and purpose. Let us sum it up in a modern way: how can we find purpose in nonsense, if we renounce consolation in a life after life, where heavenly justice prevails to give us what we were denied in this life. Is there a better life for us? Is there freedom?

V.M. There has to be! A person should truly wish for changes and improvement. Time of revolutions and big cleanups is gone. Revolutions today are nothing more than mere interest and I believe that nihilist spirit has not caught root in most people. One should clean within himself. And create small and actual utopias, as would a modern philosopher say.

Željko Hubač

(Taken from an interview with Veljko Mićunović: Mikojan Bezbradica, Modern Tragedy of Search for Happiness, “Pozorišne novine“ no. 56, November 2011)

ALBERT CAMUS

ALBERT CAMUS

Born November 7th, 1913 in Algeria son of French ‘pied-noir’ settlers Camus grew up in poverty in the proletarian neighbourhood of Belcourt in Algiers. His natural talent was spotted by teacher Louis Germain who helped the young Camus win a high school scholarship. Camus would later dedicate his 1957 Nobel Prize acceptance speech to Germain... He completed his licence de philosophie (BA) in 1935; in May 1936, he successfully presented his thesis on Plotinus, Neo-Platonism and Christian Thought, for his diplôme d’études supérieures (roughly equivalent to an M. A. thesis). Camus joined the French Communist Party in the spring of 1935, seeing it as a way to “fight inequalities between Europeans and ‘natives’ in Algeria.” Camus was never a Marxist and was against the ideas of Lenin and Stalin. However, it was true that to work with other socialist intellectuals it would have to be through the Algerian Communist Party. He would later be expelled from the Party for his postion of support for native Algerian nationalism and after that he went on to be associated with the French anarchist movement. In 1938, Camus became a reporter for a left-wing newspaper Alger Republicain, which was closed when the Second World War broke out. In 1940, Camus moved to Paris to work for Paris-Soir as a typesetter. In Paris Camus found time to persue his writing. The Stranger and The Myth of Sisyphus was published in 1942 and brought Camus notoriety within literary circles. The essay The Myth of Sisyphus expounds Camus’s notion of the absurd and of its acceptance with “the total absence of hope, which has nothing to do with despair, a continual refusal, which must not be confused with renouncement - and a conscious dissatisfaction”. Meursault, central character of The Stranger, illustrates much of this essay: man as the nauseated victim of the absurd orthodoxy of habit, later - when the young killer faces execution - tempted by despair, hope, and salvation. From 1944, Camus reached his widest audience by writing for and editing Combat, the underground newspaper of the Resistance. In 1947 Camus retired from political journalism and, besides writing his fiction and essays, was very active in the theatre as producer and playwright (e.g., Caligula, 1944). He also adapted plays by Calderon, Lope de Vega, Dino Buzzati, and Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun. His love for the theatre may be traced back to his membership in L’Equipe, an Algerian theatre group, whose “collective creation” Révolte dans les Asturies (1934) was banned for political reasons. Camus was awarded The Nobel Prize for Literature in 1957 “for his important literary production, which with clear-sighted earnestness illuminates the problems of the human conscience in our times”. He was the second-youngest recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature, after Rudyard Kipling, and the first African-born writer to receive the award. Specifically, his views contributed to the rise of the philosophy known as absurdism. He wrote in his essay “The Rebel” that his whole life was devoted to opposing the philosophy of nihilism while still delving deeply into individual freedom. His austere search for moral order found its aesthetic correlative in the classicism of his art. He was a stylist of great purity and intense concentration and rationality. Other works – novels: The Stranger (1942), The Plague (1947), The Fall (1956), A Happy Death (written 1936–1938, published posthumously 1971), The First Man (incomplete, published posthumously 1995); plays: Caligula (performed 1945, written 1938), The Misunderstanding (1944), The State of Siege (1948), The Just Assassins (1949), Requiem for a Nun (adapted from William Faulkner’s novel, 1956), The Possessed (adapted from Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel by the same name, 1959). He also wrote non-fiction books, short stories, essays…

Sources:

Nobel Lectures, Literature 1901-1967,

Editor Horst Frenz, Elsevier Publishing Company, Amsterdam, 1969

www.camus-society.com

en.wikipedia.org

VELJKO MIĆUNOVIĆ

VELJKO MIĆUNOVIĆ

Veljko Mićunović was born in 1986. in Bar, Montenegro. He graduated theatre directing on Belgrade University of Drama Arts, in the class of Egon Savin. He worked as an assistant director with Jiri Menzel (Marry Wives of Windsor) and Paolo Magelli (Italian Night). Debut performance is Don’t walki around naked (Slavija Theatre), followed by directing the play In the hunt for cockroaches (Yugoslav Drama Theatre), Othello (Theatre City Budva-Zeta-Festival MESS), Auditor, Gogol (Montenegro National Theatre), and The life is in front of you (Belgrade Drama Theatre), with which he guest toured on several theater festivals in the country and abroad.

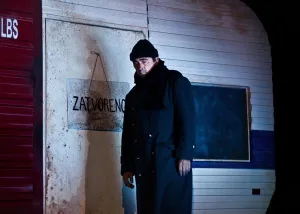

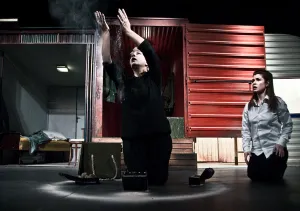

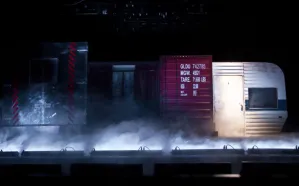

Premiere performance

Premiere, December 10, 2011 / Main stage

Translation Mira Dimitrijević

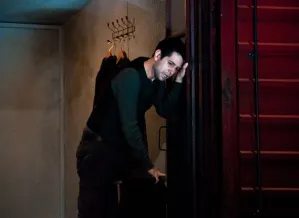

Director Veljko Mićunović

Dramaturge Željko Hubač

Set Designer Vesna Štrbac

Costume Designer Marina Medenica

Music Selection Veljko Mićunović

Stage Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović, Phd

Stage Movement Tamara Antonijević

Sound Designer Vladimir Petričević

Premiere cast:

Mother Ljiljana Blagojević

Maria Vanja Ejdus

Martha Marija Vicković

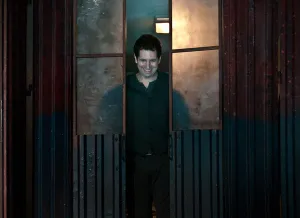

Jan Mihailo Laðevac

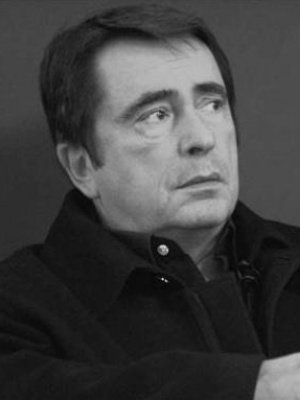

Old Man Milan Gutović

Producer Ivana Nenadović

Stage Manager Sandra Žugić Rokvić

Prompter Sandra Todić

Assistant Costume Designer Olga Mrđenović

Light Operator Srđan Mićević

Make-up Dragoljub Jeremić

Set crew Chief Nevenko Radanović

Sound Operator Roko Mimica

SET AND COSTUMES WERE MANUFACTURED IN THE WORKSHOPS OF THE NATIONAL THEATRE