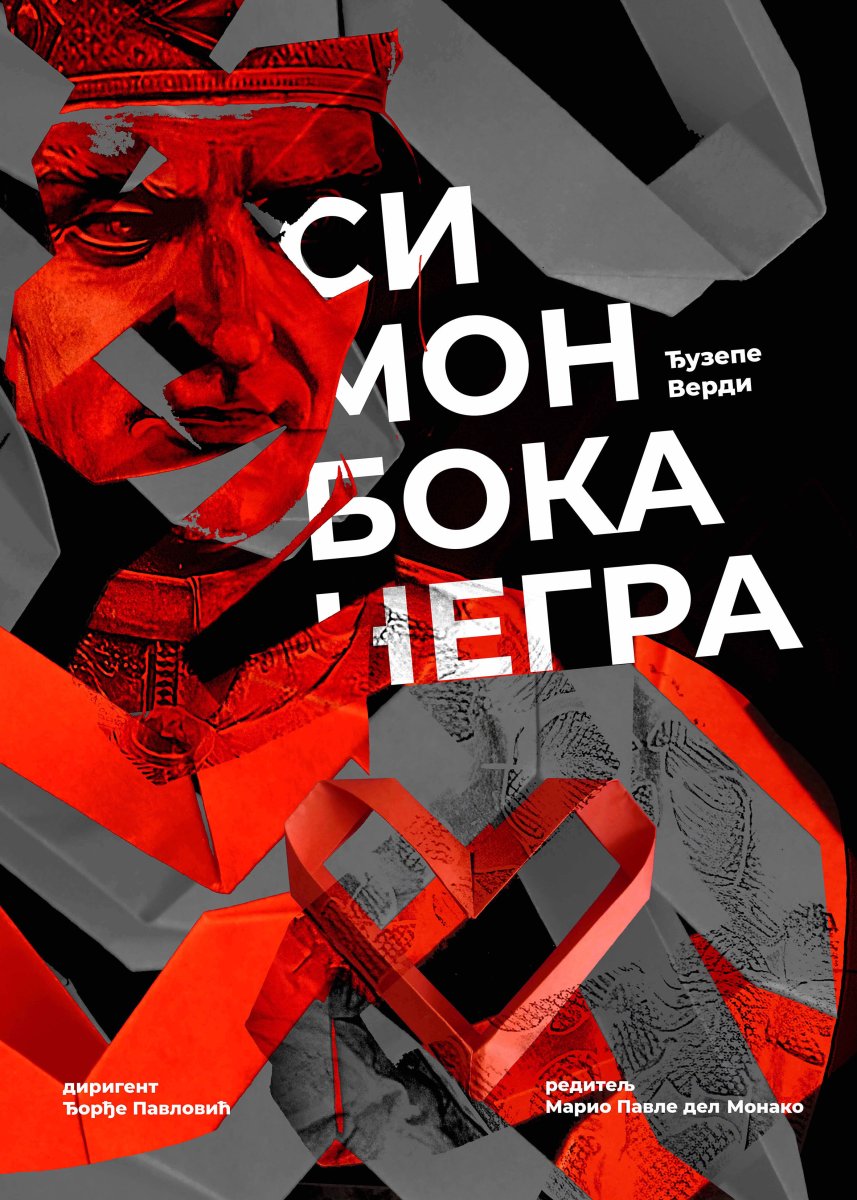

Simone Boccanegra

opera by Giuseppe Verdi

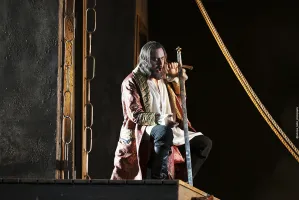

Simon Boccanegra – Baritonо Nobilе

In 1879, the publisher Giulio Ricordi wrote to Giuseppe Verdi (1813 – 1901) hoping to motivate him to revise the 1857 version of the opera Simon Boccangra and stage it again. “I have received a large parcel which I assume is the score of Simon”, Verdi replies “you will find it intact”. However, Ricordi did not abandon the idea of making the composer change his mind, who had decided that Aida would be the last work in his career, and introduced him to the composer and librettist Arrigo Boito (1842 – 1918). Boito proposes Shakespeare’s Othello for Verdi’s next opera, and thus arouses the composer’s interest not only in composing a new piece, but also the hope that in this talented librettist and great connoisseur of Shakespeare’s work he has found a collaborator worthy to be entrusted with the revision of Simon Boccanegra.

The first version of this opera whose librettist was Francesco Maria Piave (the premiere took place on March 12, 1857 at the La Fenice theatre in Venice), was created at a time when the already famous composer reached the peak of his world popularity with Rigoletto (1851), Il Trovatore (1853) and La Traviata (1853). Il Trovatore, based on the medieval knight play of the same name by Antonio García Gutiérrez from 1836, appealed to Verdi because of its style resembling the work of Victor Hugo (on whose works Verdi’s operas Ernani and Rigoletto were based), whom the composer greatly appreciated, among other things, because Shakespeare was a role model in theatrical work for both Hugo and Verdi. It is not unusual that a few years later he again used one of Gutiérrez’s works as the basis for his new opera - the play Simon Boccanegra (1843) set in the 14th century. He was attracted by dramatic twists, surprising moments, the palette of the most diverse emotions that needed to be brought to life musically, i.e., the contrasts arising from all of the above, which gave Verdi an incentive to compose and enabled him to achieve chiaroscuro as in Rigoletto, the effect of alternating light and darkness. With an artistic intervention, Verdi puts historical events at the service of the story he wants to tell, which implied a departure from historical facts, and creates an opera of very complex content that summarizes several decades of the turbulent history of Genoa led by the equally complex character of Boccanegra as its Doge. It intertwines private and political life, love, duty to the people and the state, intrigues, conspiracies, mistaken identities...

Gutiérrez already in his drama combines two historical figures in the character of Boccanegra - the doge and his corsair brother - a sea captain who fought in the service of other countries. Like Rigoletto, he is a man of the people to whom the nobleman Fiesco refuses to give the hand of his daughter Maria, with whom Boccanegra has a child. Simon, although without political ambitions, accepts to become doge hoping that this position will also make Fiesco accept him. But Maria dies and the desperate Boccanegra, now as the doge who will eternally long for the sea (whose motif Verdi weaved into the opera), accepts his duty and as an idealised Verdi’s character with a “noble vision of peace” and a desire for unification tries to reconcile the confronting parties - Genoa and Venice, the nobility and the people, and finally his own family. Boccanegra’s and Maria’s child, their daughter Maria (i.e. Amelia), who by game of destiny went missing as a child, from the very beginning is a guarantee for the reconciliation between Fiesco and Boccanegra, i.e. between the aristocracy and the people, which will take place by the end of the opera.

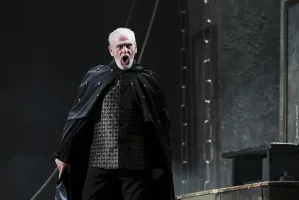

This is an opera that rests on the dark male voices with which the composer coloured this grave story. The title character is again a Verdi baritone. Unlike his other operas, famous for their arias, in Simon Boccanegra there are extraordinary and exciting duets, and his effort to achieve greater expressiveness of the text, according to Alain Duault, represents Verdi’s step ahead of his time.

The premiere of Simon Boccanegra in 1857 was not the success that Verdi expected. When, more than twenty years later, he and Boito resumed work on this opera, it was almost like composing a new work. Among the many changes they introduced, the most significant is the completely new scene in the Council Chamber, which also becomes the central part of the opera which Harry Powers calls “the great choral fresco”. Verdi’s inspiration for this scene were, as he said, “two magnificent letters from Petrarch” addressed to the doges of Genoa and Venice in which he calls for peace and unification, and Boccanegra himself reads Petrarch’s letter to the audience in the opera. “This is exactly what the original opera so conspicuously lacked” Julian Budden notes “a solo in which the protagonist could show all his moral and spiritual strength to reveal himself as the noblest of all Verdi’s noble baritones (baritoni nobili)”. Boito, on the other hand, will deepen the character of Paolo, making him, as only he could, the main villain of the opera, the one who engages in intrigues and the one who tempts the other characters in the play, thus announcing Verdi’s Iago.

The premiere of Verdi’s and Boito’s Simon Boccanegra (held in Milan’s La Scala on March 24, 1881) was greeted with great interest by the audience that came from all over Italy, but also from London and Paris. From that day until today, Boccanegra is in the repertoire of opera houses around the world, and it will be performed for the first time on the stage of the National Theatre in Belgrade in 2024.

Vanja Kosanić

Verdi’s immortal hero

By the 13th century Genoa emerged as one of Italian powerful citystates. Internally, Genoa was overcome with civil unrest between the aristocrats (Patricians) and the commoners (Plebians). The Patricians controlled the government while the Plebians were prevented from running for any political positions. In the 14th century, after an uprising the Plebians took over the authority and created a new head of state called a Doge as their leader.

Though in the opera, Simon was portrayed as coming from humble birth and becoming a corsair, historically he was born into a relatively powerful Plebian family. Boccanegra Family, wealthy Genoese family of merchants, played an important role in two great “popular” (democratic) revolutions, one in 1257 and the other in 1339, and furnished several admirals to the Genoese republic and to Spain. Guglielmo Boccanegra, who in 1257 became a virtual dictator of the Republic of Genoa when an insurrection against the government of the old aristocracy made him gain the control of the republic. During his reign Genoa was at its peak so historians call him Guglielmo the Great. Guglielmo Boccanegra was also the commissioner of the building of Palazzo San Giorgio, the future seat of republican power in the republic. Simone’s brother, Egidio, was a grand admiral in the service of Alfonso XI of Castile, and inflicted a memorable defeat on a Moroccan fleet off Algeciras in 1344.

In 1339 another popular revolution resulted in the election of Simone Boccanegra (1301–63) as the first Genoese doge. His election marked a new age in the history of Genoa. He formed a new government and engaged a war against the guelphs but with the old patriciate excluded from power, a new class of mercantile houses arose: Adorno, Guarco, Fregoso, and Montaldo. He was a man of the people who continuously struggled to keep civil unrest in Genoa from destroying the city, on top of fighting other Italian city-states for the domination of trade routes. Deposed in 1344, Simone fled with his family to Pisa, where Simone’s brother Niccolò was “Capitano del popolo”, their mother having been a Pisan aristocrat. He was succeeded by two short termed Doges until he regained power in 1356 with the aid of the Visconti, the rulers of Milan. He ruled until 1363. when according to tradition, he was poisoned by Adorno and Fregoso famillies at a public banquet in celebration of the King of Cyprus’ visit to Genoa. He was buried in the church of San Francesco in Castelleto in Genoa. Simone Boccanegra’s tomb was decorated with a remarkable funeral sculpture, depicting him with extraordinary realism in his features as if he was still in power. This sculpture is now in the Museum of Sant’Agostino. After winning the election that followed Simon’s death, Gabriele Adorno, did succeed him as Doge, in the opera and in real life. He will become the fourth Doge of Genoa. He remained in the position until August 13, 1370, when he was deposed by the people of Genoa.

The politics in the story of Simon Boccanegra were very similar to the political situation in Italy in the 1830s. Opera provided an intriguing way for Verdi to comment on Italy’s existing situation.

Jovan Tarbuk

A Word from the Director

The inexorable tragedy of life is that it happens either too soon or too late. Our loved ones leave us too soon, while we are often able to forgive others too late or we are forgiven too late. Verdi’s own life is also a testimony of the invasive and almost violent game of fate, as he buried his wife, his first-born and even second-born child as a very young man.

As an alternative symbolic title, the opera “Simon Boccanegra” could also be called “The Tragedy of Deprivation”. The characters are deprived of relationships between lovers, parents and children, father-in-law and son-in-law, blessings and the cursed, all within the tensions of the confronting republics, Genoa and Venice, and the strained relations between the people and the aristocrats. At the beginning of the 14th century, people encountered a period of Great Famine, accompanied even by cannibalism; trust in the ruling class is shaken, as is trust in the church itself.

In this quasi-musical stage film, not only are we witnesses to the revival of a gem from the golden era of opera art, but we are relentlessly, enigmatically and ecstatically invited to be interlocutors and accomplices in the synesthetic enigma of mutually intersecting life paths.

Above all, the questions arise: is a man’s personal loss the main component that leads us to destruction and self-destruction, and is it actually the final exhalation of the hope of a mere mortal? Or is it precisely then that we are given the chance to light the way forward for ourselves and others, since we have witnessed both personal and collective pain and have seen in others only an alternative instance of ourselves? Does losing another mean losing oneself and how powerful is the transformative power of loss?

Synopsis

Prologue

Genoa in 1339

It is night. In the square (piazza) where the church of San Lorenzo and the palace of the leader of the aristocratic party, Fiesco, are located, Paolo, the leader of the plebeian party, which is preparing a coup d’état and the removal of the doge, talks with Pietro about the election of a new doge. Paolo suggests Simon Boccanegra who recently restored Genoa’s naval glory by driving African pirates from the seas.

Pietro leaves and Boccanegra appears. As a man without political ambitions not willing to oppose Fiesco, he is initially reluctant to accept the appointment, but Paolo tempts him with the fact that when he comes to power, he will be able to marry the girl he loves, Fiesco’s daughter Maria, with whom he has an illegitimate child and who is therefore held captive by her father. Boccanegra agrees. When he leaves, a crowd of people enter led by Pietro. He and Paolo persuade them to support Boccanegra and then leave together.

Fiesco exits the palace. His daughter Maria has just died and he is grieving and cursing Simon (aria “A te l’estremo addio... Il lacerato spirito”). Boccanegra comes and asks Fiesco to forgive him for his sin. He is ready to do so if Simon gives him the child Maria gave birth to, but he explains to him that he does not know where the child is because Maria entrusted it to an old woman. Fiesco then refuses to forgive him. Boccanegra enters the palace, demanding to see Maria but to his horror discovers that she has died. In the distance, he hears the people cheering his name as the new doge. Paolo and Pietro arrive to tell him he has been chosen, the crowd cheers to Boccanegra and the bells toll in his honour as he mourns.

Act One

Scene One

Genoa in 1363. In the garden of the Grimaldi palace.

More than twenty years have passed. Simon Boccanegra is still the doge and Fiesco, under the false name of Andrea, is plotting against him.

At sunrise, in the garden of the Grimaldi palace, a young woman admires the beautiful surroundings (aria “Come in quest’ora bruna sorridon gli astri e il mare”). She is Boccanegra’s illegitimate daughter, the child who once went missing. She now goes under the name of Amelia Grimaldi and is completely unaware of her origin. She thinks of Andrea (actually her grandfather) only as of her patron. Her lover, Gabriele Adorno, arrives. Amelia is worried about him because he is plotting with Andrea and other Genoese against the Doge. The two of them sing about their love (duet “Vieni a mirar la cerula”). Pietro arrives, announcing Boccanegra’s visit. Amelia explains to Gabriele that Boccanegra wants her to marry Paolo. She naturally wants to marry Gabriele and begs him to ask Andrea’s blessing for their wedding.

As Gabriele prepares to leave, he meets Fiesco (i.e. Andrea) and asks him for Amelia’s hand in marriage. Fiesco draws his attention to the fact that Amelia is not Count Grimaldi’s daughter, but a foundling who assumed the role of his child, in order to save the family’s wealth from the doge’s confiscation (two of Grimaldi’s sons are in political exile). Gabriele, although an aristocrat, does not give up his intention and Fiesco blesses him agreeing to their marriage.

The trumpets announce the arrival of Boccanegra and Fiesco and Gabriele leave in a hurry. Simon came to speak on behalf of Paolo, but Amelia tells him that she is in love and does not want to marry Paolo, who is only after the Grimaldi’s wealth. Boccanegra is ready to forgive her brothers who rebelled against him, however, she explains that she is not a Grimaldi by birth but she was adopted (duet “Orfanella il tetto umile”). Boccanegra realises that she is his long-lost daughter, named Maria, and this is confirmed when they compare pictures of her mother. They are overcome with joy because of that revelation.

Simon tells Paolo that he has to give up his marriage with Amelia, but he does not accept such a decision and arranges with Pietro to kidnap her.

Scene Two

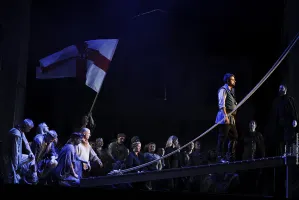

The Council Chamber

Boccanegra presides over a council consisting of patricians, plebeians (including Paolo) and several officers. The Doge conveys to the representatives of the nobility and the people the message of Petrarch, who seeks peace between Genoa and Venice, but they rebel against it. At the same time, in the distance, the cries of the people are heard shouting “Death to the nobility” and “Death to the Doge” and Gabriele is attacked. Paolo prepares to flee, but Boccanegra orders the door to be guarded and sends a herald to tell the gathered crowd that he is waiting for them to come. They enter the town hall demanding Gabriele’s blood because he killed Lorenzino who tried to abduct Amelia. Believing that Lorenzino was acting on Boccanegra’s instructions, Gabriele tries to attack Boccanegra himself.

Suddenly, Amelia rushes in and stands between the two. At Simon’s request, she tells the true story of the abduction and how she managed to escape. Without naming him, she accuses Paolo. A fight almost breaks out between the two parties in the council and Boccanegra angrily steps between them demanding peace: (Aria: “Plebe! Patrizi!”). He manages to quell the rebellion while Paolo plots revenge (sextet with choir).

Gabriele hands over his sword to Boccanegra who informs him that he will be kept in prison overnight until it is established what really happened. Simon who has realised that Paolo is the culprit of the abduction asks him to join in uttering the curse on the kidnapper. Paolo reluctantly joins in, horrified. The whole ensemble unites in the curse and Paolo tries to flee.

Act Two

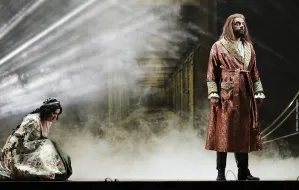

In the chamber of the Doge’s palace

Paolo enters the palace to take revenge on Boccanegra and pours poison into his glass. Gabriele and Fiesco, who are locked in another room, enter. Paolo tries to convince Fiesco to murder the doge, but he refuses and leaves. Then Paolo convinces the gullible Gabriele that Amelia is Boccanegra’s lover. Gabriele, who is left alone, is torn by anger, despair and jealousy (Aria: “O Inferno! ...Sento avvampar”).

Enters Amelia who now lives in the palace as Boccanegra’s daughter. When Gabriele sees her, he accuses her of being the Doge’s lover. She assures him that she is faithful to him and that she cannot yet tell him about her relationship with Boccanegra. Hearing that Boccanegra is approaching, Gabriele hides, adamant to murder him. Boccanegra finds Amelia crying and, to Boccanegra’s great dismay, she confesses to him that she loves Gabriele, who is plotting against him with his family. Simon promises to forgive Gabriele if he repents. After she leaves, he drinks the poisoned wine that Paolo poured for him and falls asleep.

Gabrielle comes out from his hiding place and finds Boccanegra sleeping. He is about to kill him but Amelia returns and stops him. Boccanegra wakes up and the two men confront until Simon blurts out that Amelia is his daughter. Gabriele bows to him, full of remorse imploring Amelia to forgive him. Simon realises that their marriage could lead to a reconciliation of the conflicting parties.

Outside uproar is heard because a rebellion of the patricians (noblemen) has broken out, who want to oust the Doge from power. Boccanegra tells Gabriele to go and join his friends but he now refuses to fight against him and agrees to take a message of peace to the rebels. In return Boccanegra rewards him by giving him Amelia’s hand.

Act Three

The grand hall inside the palace overlooking the sea

Peace has been restored and the joyous shouts of the people can be heard outside. Fiesco has been released. On his way out, he meets Paolo, who has been captured and sentenced to death for organising a rebellion because the doge, whom he proposed, never let him take part in the government. Paolo reveals to Fiesco that he poisoned Boccanegra. Distant voices are heard celebrating the wedding of Gabriele and Amelia. Paolo is taken to be executed and Fiesco goes into hiding. Boccanegra enters, unsteady, feeling sick as the poison sets in. Fiesco appears and reveals to him his true identity and Boccanegra tells him who Amelia really is and the two men are finally reconciled. Unfortunately, Fiesco tells Boccanegra that he has been poisoned (Duet: “Piango perche mi parla”).

Amelia and Gabriele enter with the wedding procession and Simon tells her that she is Fiesco’s granddaughter. The peace is restored both in the family and in the town - between patricians and plebeians. Their joy at marriage and reunion is interrupted by the realisation that Boccanegra is about to die. He blesses them and only has so much time left to name Gabriele his successor before he dies. Fiesco announces to the people that Gabriele Adorno is their new doge. They ask for Boccanegra but Fiesco tells them that he has died and they pray for him.