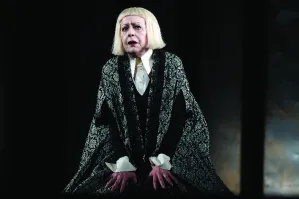

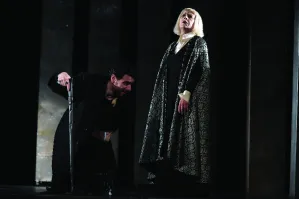

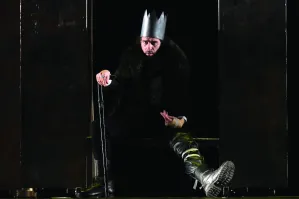

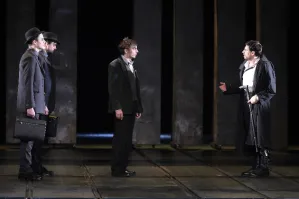

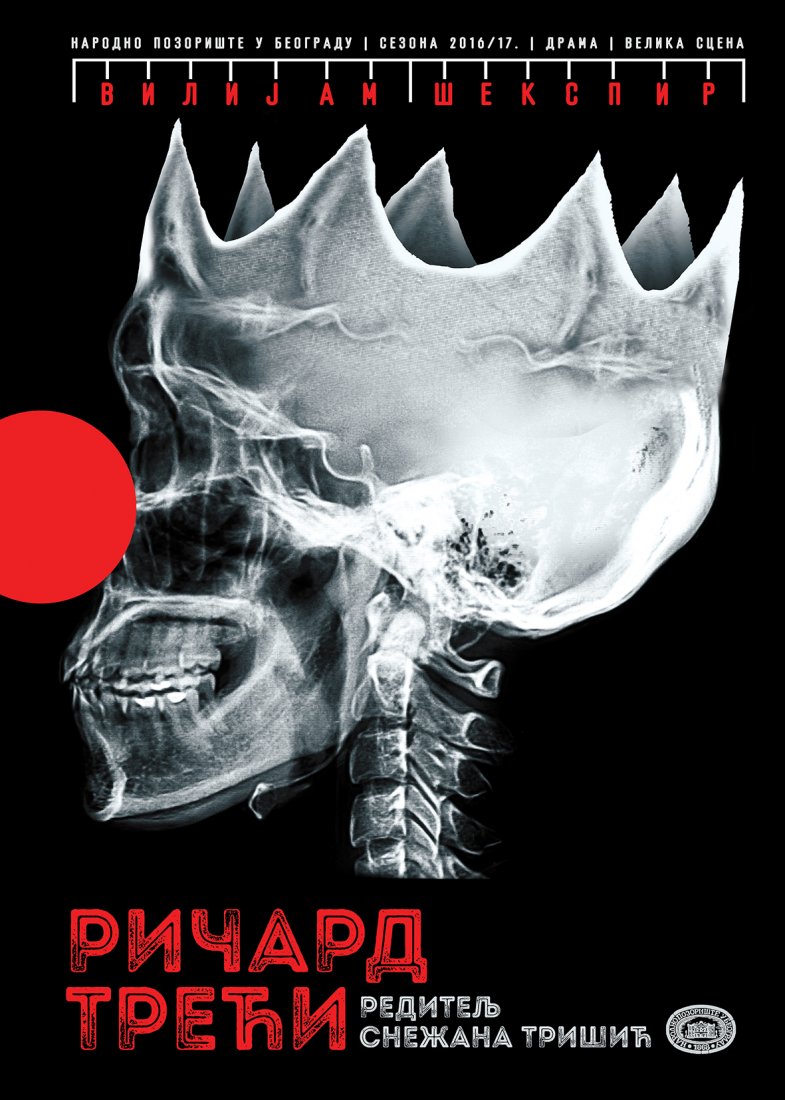

Richard the Third

drama by William Shakespeare

SNEŽANA TRIŠIĆ

SNEŽANA TRIŠIĆ

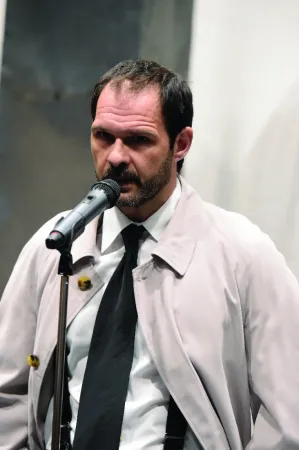

Snežana Trišić was born in Belgrade in 1981. In 2009, she graduated from the Department of Stage and Radio Directing at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, in the class of Professor Nikola Jevtić and Assistant Professor Alisa Stojanović. In period between 2013 and 2015, she worked as a Stage Director in the National Theatre in Subotica. Since 2015, she has been working as an Assistant Professor with Professor Ivana Vujić at the Department of Stage Directing at the FDA in Belgrade. Selection of her productions: Family Stories by Biljana Srbljanović (Faculty of Dramatic Arts, 2007); The Class by Matjaž Zupančić (National Theatre of Republika Srpska, Banja Luka, 2009); Samoudica by Aleksandar Radivojević (Theatre Atelje 212, 2009); Hedda Gabler by Henrik Ibsen (National Theatre in Belgrade, 2011); How Much is Pate? by Tanja Šljivar (Theatre Atelje 212, 2012); A Miracle in The Viper’s Sweetheart by Ante Tomić / Maja Pelević (National Theatre in Subotica, 2012); The National Drama by Olga Dimitrijević (Bora Stanković Theatre in Vranje, 2012); Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi / Jelena Mijović (City Theatre Podgorica, 2013); Mr. Dollar by Branislav Nušić / Dimitrije Kokanov (National Theatre in Subotica, 2014); Rhinoceros by Eugene Ionesco (National Theatre Kikinda, 2014); Kasimir and Karoline Odon von Horvath (Theatre Atelje 212, 2014); Noises Off by Michael Frayn (National Theatre in Subotica, 2015); What Happened after Nora Left Her Husband; or Pillars of Society by Elfriede Jelinek (Yugoslav Drama Theatre, 2015); The Gorge by Žanina Mirčevska (National Theatre Kikinda, 2016); Terrorism by Vladimir and Oleg Presnyakov (Belgrade Drama Theatre, 2016). Snežana won numerous awards and recognitions for stage directing at renowned festivals in the country (Yugoslav Theatre Festival, Užice; Festival of Classics, Vršac; Festival of Vojvodina Professional Theatres; Festival of Serbian Professional Theatres “Joakim Vujić”; Days of Comedy Festival, Jagodina; PIP, Aleksinac, JoakimInterFest, Kragujevac; Theatre in Single Action, Mladenovac, etc.), as well as abroad (Children Theatre Festival, Kotor; International Festival of Theatre Schools in Brno, Czech Republic). For Kasimir and Karoline, she won Sterija’s Award for Stage Directing in 2015. Snežana also won recognitions for best stage director, namely “Ljubomir Muci Draškić” Award awarded by Atelje 212 and the Award of the City of Belgrade, as well as the “Hugo Klein” Award for best student in her generation at FDA (2007). As a recipient of Kennedy scholarship (John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, U.S. State Department), Snežana Trišić participated in the programme for stage directors and in numerous workshops in Washington D.C. and Chicago, 2010. In 2013, she enrolled into doctoral programme at the FDA in Belgrade. Snežana attended the International Seminar for Stage Directors, organised by ASSITEJ Germany in cooperation of ASSITEJ International, in the Schnawwl Theatre for Children and Young People in Mannheim in 2015.

EXPOSING EVIL

“I see Shakespeare as a modern playwright, who lives somewhere nearby and I would probably be surprised not to see him at our premiere,” says Snežana Trišić, a stage director, in an interview for The Theatre Magazine. This comment has been established in theatre practice – for more than four centuries, viewers have found Shakespeare’s works relevant and understandable. Because, as Jan Kott wrote in his famous study Shakespeare Our Contemporary, “Shakespeare is like the world, or life itself. Every historical period finds in him what it is looking for and what it wants to see.“ It is not only because of the great dramatist's superiority as a poet, which would make his relevance exclusively aesthetic, among other classical works; Shakespeare is great in this manner in his poems, sonnets and comedies, in which he still evokes images of the Renaissance utopia. However, in his history plays, the main hero is history itself – unprocessed, consisting of people who mercilessly fight for power. Among his history plays Richard III is taken as a pattern for all later works. Richard III is Shakespeare’s early play, written around 1592, soon after Marlowe’s Tamburlaine (1587) which marked the beginning of Elizabethan drama period. These two plays present criminal characters that have not been known in the history of drama before. Although there was quite a number of villains and murderers in medieval plays and mysteries, they were presented only as tools in God’s hands. Crimes committed by those executioners, bandits and criminals (and some of them where noblemen and kings), were seen as God’s punishment for sins committed by society, or even the state. The villains were typical characters. Shakespeare’s Richard III, however, is presented as a powerful individual (even more so than Tamburlaine), and this novelty introduced criminal characters, violence and murders to Elizabethan stage, thus strongly attracting and fascinating contemporaries – playwrights and city theatregoers as well – until Puritans closed all the theatres in London in 1642. Explaining why the crime managed to impose itself to theatre (which was still looking for new theatrical forms) and became the principle of every tragedy, Duvignaud finds that fascination with modern criminal can be explained by emergence of atypical (anomic) personality at the time when reality was changing quite rapidly and the existing norms of behaviour originated from old and petrified (medieval, feudal) system. “All Elizabethan drama heroes were condemned to suffer and be miserable precisely because of their individualism… They are adamant in proving that they are free because of solitude imposed to them.” The freedom to live and act according to their own will, to experience what was never experienced before, represents the first words that all heroes in Shakespeare’s plays say as soon as they appear on stage. Freedom can be expressed with “I am determined to prove a villain”, as does Richard III in the first soliloquy. (German essayist Rudiger Safranski says, “Evil belongs to the drama of human freedom. It is the price of freedom.”) Jan Kott has seen history as a grand staircase on which an individual ascends to power through successive steps of murder and treachery until one is eventually pushed off the top step by someone coming up from below. He called it the Grand Mechanism. The history is just a succession of kings. Richard III is the intelligence and conscience of the mechanism, his revolution lies in the fact that he reveals the order. Duvignaud said that his immense willpower questions the world order. The actual Richard III was a part of the Grand Mechanism just like all his royal ancestors were; he did not commit any more or less crimes than Richard II, John I or Edward II. Even Sir Thomas More, Hall and Holinshed – authors of chronicles about Richard III, which were used as sources by Shakespeare for the play, did not question the perpetual constancy of the Grand Mechanism. However, it was only the Shakespeare’s character who managed to make history lively and present. Only the work of art, a play, offered the experience of identification with Richard III to a modern viewer in the turbulent times of Elizabeth I and James I. Viewers did not merely see a villain in Shakespeare’s Richard; instead, they saw a free individual who was guided by his own willpower, even when it led him to crime and destruction. The play enabled the writer, and a viewer as well, to leave the frame of their own and tolerated experience. This is what Jean Duvignaud and Jan Kott spoke about when they claimed that Richard III announces Hamlet (1602); and that after reading Hamlet, Richard III could be understood as a philosophical play. Today, we do not have a clear vision of the Grand Mechanism. It is not only an order which comes from the past, it has penetrated all aspects of modern life; we can feel its presence in everything surrounding us. Great anomic individuals from Shakespeare’s age, powerful individuals, as well as characters presented by Goethe, Schiller and Ibsen, have dissipated into fragmentary “identities”. The only constant that connects us with the past is the presence of evil. Therefore, while answering a journalist’s question about intensity of evil today, the stage director Snežana Trišić says, “Evil changes its form and rhetoric, but it does not diminish. The evil is present everywhere, on street corners, on shelves in shops where the prices are, or at the gas station nearby, in every news of the manipulative media, at most www addresses, in every spin, in every lie, on ballot papers, in advertisements of exotic destinations, in bankrupt and devastated factories, on borders closed with barbwire, etc. Richard III is open about his crimes; he reveals his intentions and explains them, he announces them. He makes the viewers his witnesses and accomplices in crime, in which he breaks the order and becomes its ruler in the alluring and dark feast of devious politics. Evil becomes one of main conditions of existence.”

Slavko Milanović

ABOUT RICHARD III

In the beginning there is a strong resistance – Richard III is a repulsive and revolting play that should be immediately forgotten. The main character is both physically and mentally deformed, an antihero, a monster, a killer and a Machiavellian, a brother’s murderer, a child murderer, a power-thirsty monster, a maniac, a necrophiliac and what not. The play’s theme – a series of crimes, a Danse Macabre, a feast of death of a political monster, which Jan Kott ingeniously named the Grand Mechanism of power. General atmosphere – a nightmarish night of death and crime, a hellish poem of terror and hopelessness. Primary colour – dark and blood, a sea of blood in which everything drowns. In a word, it is a world of this play, worthy of Dante’s Inferno. Without a crown, or even with it, the main character keeps walking over the corpses as if in the Grand-Guignol Theatre performance or in a horror film. At certain moments, the play seems it is a farce or a grotesque instead of a historic tragedy. In addition, as researchers have established, the real Richard III was quite the opposite of the character that Shakespeare devised as “historical” king of villains…

Judging from the above, the play could not be saved by anything. However, there was a miracle. Right here, in this extremely dangerous slippery ground, in the sphere of suppressed and almost completely absent humanity, Shakespeare expressed the full force of great poet’s skill. He manages to set a surprising equilibrium and make all the dangerous flaws into virtue, in an impressive way... The question is – how could it be possible… Shakespeare has given his completely freakish hero, the crowned king of evil and crime, such an appealing and sharp intelligence, such bold spirit, strength of self-control and irony, eloquence and the power of persuasion, that the audience becomes deeply abhorred and afraid of him, but at the same time, they fear for outcome of his (Richard’s) “endeavours” and, what’s more, they cheer for him… namely, a viewer experiences both pro and contra catharsis made after the prescription of maestro Shakespeare, the unsurpassed healer, analyst and diagnostic of soul’s pains and therapy. This is why this “anti-play”, as a testing ground, as a grain of temptation, as a challenge to test oneself, to question and prove one’s powers, is so often revisited by the boldest of artists, researchers and experimenters throughout the world and the audiences everywhere congregate in auditoriums whenever Richard III is on the repertoire. In the end, there is a strong experience – Richard III is a great or, should we say, a brilliant play one remembers until the end of one’s life.

Dušan Mihailović (from the Programme of 1972 staging)

Richard III on the National Theatre's Stage

Shakespeare’s Richard III, translated by Laza Kostić, found its way to the National Theatre’s repertoire for the first time on 30th January 1898. The staging was very ambitious; new set and costumes were obtained from Vienna, while Milorad Gavrilović, the leading actor at the time, directed it and interpreted the leading role. The reviews stated that Gavrilović interpreted the role of Richard convincingly, passionately and rationally, however he failed to portray sufficient amount of evil and demonic character, but both he and Vela Nigrinova (Lady Anne) “were superb at each situation (especially in the second scene of the first act) that gave opportunity to illustrate conflicts, feelings and passions”. It is noteworthy to mention the ninth performance, given on 2nd March 1901, in which a guest artist from Russia performed, it was none other than Prince Alexander Ivanovich Sumbatov Yuzhin, a member of the Imperial Theatre of Moscow. The press wrote, “Yuzhin was superb in this role as well. One could see that there was deep and comprehensive analysis in all scenes. The artist was particularly successful in the dreadful fifth act, when at night all the victims haunt his character. Although the character he interpreted was repulsive and left an uncomfortable feeling with the audience, the audience, who appreciated Yuzhin’s artistic accomplishments, gave him cordial applauses after each act, and even twice in one of the acts. On that evening, the theatre was again packed to capacity”. The cast consisted of 38 actors and numerous “lords and courtiers, knights, ghosts, soldiers, etc.”, which was quite an endeavour for the ensemble at the time. Five years later, on 18th and 20th May 1906, Mihailo Isailović, who was a stage director in the Düsseldorf Theatre, interpreted the role of Richard. Upon success in German theatres, he interpreted the role in Serbian language for the first time, but it did not stop him from interpreting the “demonic side of villain’s damned soul” successfully. It was the last performance of this staging, which had 18 performances. Ljuba Stanojević was the next Richard III in a production he directed himself. The premiere took place on 30th October 1908. It was noticed that Stanojević’s interpretation presented “a warmer, softer and nobler Richard”. This staging was on the repertoire only until the end of the season; it had 4 performances. After the Great War, Richard III made it to the repertoire again on 4th May 1922, and again Laza Kostić’s translation was used. The stage director and protagonist was Mihailo Isailović. Leonid Brailovsky designed the set and the costumes. “Acting, costumes, set – it is obvious that the production was skilfully prepared”, the reviews say and assess that Isailović “has profoundly studied Richard’s character and was brilliant with irony and cynicism”. The staging remained on the repertoire for three seasons and was performed 11 times. The next staging took place half a century later, for which a new translation was used; the new translation was done by Živojin Simić and Sima Pandurović. Dr Hugo Klein directed it, Vladimir Marenić designed the set, Božana Jovanović designed the costumes and Branislav Ciga Jerinić designed the masks. The premiere took place on 30th March 1972, with Mija Aleksić in the title role. In order to explicate Richard’s personality with situation in which he was born to and in which he lived, Klein decided to give the play a very popular theme at the time, the hippie motto “Make love not war”. The critics said that the performance was “static and neutral”, that Klein approached the play with “academic reverence”, which turned out to be more important than characters to him. Mija Aleksić interpreted Richard as “a court intrigue plotter” instead of “a bloodthirsty and ruthless killer and a power greedy king”. This production remained on the repertoire for less than two years. The last staging of this historical play took place in April 1992; Vida Ognjenović directed it, Boris Maksimović designed the set, Ljiljana Dragović designed the costumes. Predrag Vranešević composed the music and Lidija Pilipenko designed the choreography. Predrag Miki Manojlović who interpreted the leading role, as the critics said, was a sort of “a broker of theatre… not only is he a servant to inferno, he is its stage director and a leading actor, as well”. His Richard is an intrigue plotter in the beginning, only to develop, as the plot thickens, into an aggressive and arrogant “bully who stops at nothing on his way to the throne”, which he does by making “the moves of merciless impatience”. Owing to “his expertise in expressing most complex states of mind”, Manojlović succeeded in portraying what makes a monstrous king “a being”. Upon Richard’s death, his young successor appears on the stage and begins to limp burdened by the lump on his back, “Evil, therefore, does not die. It lies in the crown. Or more precisely, it lies on the path to the crown.” The whole cast was awarded with the National Theatre’s Award, while Stela Ćetković received an individual award. The staging was performed for only two seasons; it had 19 performances and was seen by 6000 people.

Jelica Stevanović

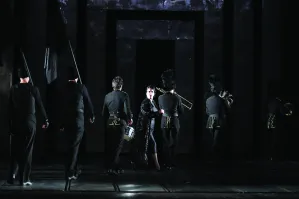

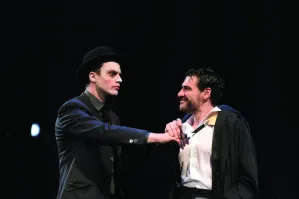

Premiere performance

Premiere 24th April 2017 / Main stage

Translated by Živojin Simić and Sima Pandurović

Stage Director Snežana Trišić

Authors of Adaptation Snežana Trišić, Slavko Milanović, Slobodan Obradović

Set Designer Valentin Svetozarev

Costume Designer Marina Medenica Vukasović

Dramaturges Slavko Milanović, Slobodan Obradović

Composer Irena Dragović

Stage Speech Ljiljana Mrkić Popović

Executive Producer Vuk Miletić

Organiser Natalija Ignjić

Premiere Cast:

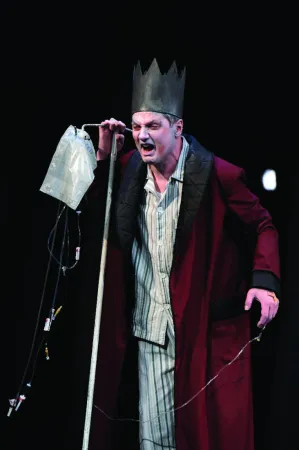

Gloucester Igor Đorđević

Duke of Buckingham Aleksandar Đurica

King Edward Nebojša Dugalić

Lady Anne Vanja Ejdus

Elizabeth Nela Mihailović

Duchess of York Svetlana Bojković

Margaret Nataša Ninković

Hastings Miloš Đorđević

Clarence Bojan Žirović

Catesby Pavle Jerinić

Richmond Aleksandar Srećković

Archbishop Branko Jerinić

Rivers Gojko Baletić

First Assassin Ivan Marković*

Second Assassin Miodrag Dragičević*

Stage Manager Saša Tanasković

Prompter Danica Stevanović

Organiser in training Sara Bubalo*

*Students of the Faculty of Dramatic Arts and the Academy of Arts

Assistant Costume Designer Olga Mrđenović

Assistant Set Designer Jasna Saramandić