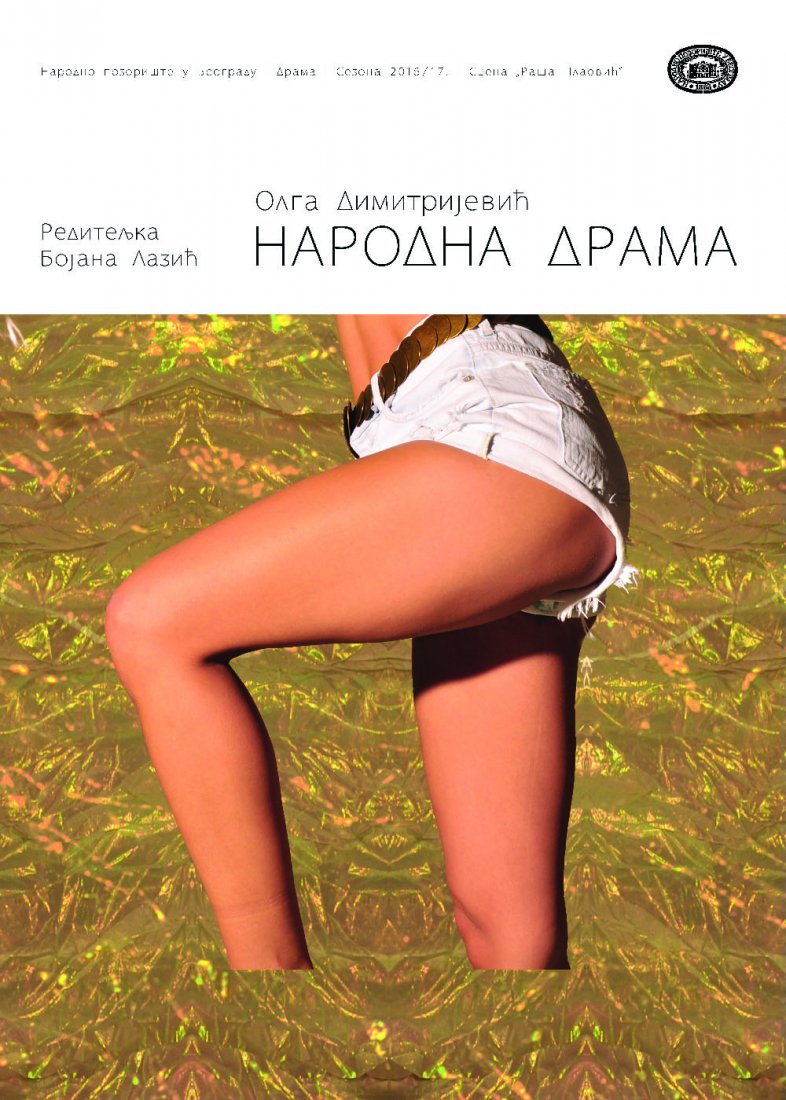

The folk play

drama by Olga Dimitrijević

HELLO, GOODBYE, FAREWELL

The Folk Play by Olga Dimitrijević has travelled a serious time (and geographical) distance to the stage of the National Theatre in Belgrade. The play was written in 2008/09; its first stage reading and premiere took place in Vranje in 2011/12, at the „Bora’s Days“ Festival, followed by tours and awards to the authors and cast at the 51st “Joakim Vujić” Festival in 2015. The playwright’s style recognizable from the The Boarding School, Workers Die Singing, and It’s so Good Seeing You Again, is present with all its elements in The Folk Play. Regarding its form, the play features tragicomic fragments; intertwined elements of past, present and the future, (either directly or through characters’ anticipation); dramatic and confessional parts are equally present; the line between verse and prose is blurred, as is the line between dialogue and stage directions... And although, almost as a rule, the playwright puts all her heroes into hopelessly dark social and political circumstances, one cannot say that Olga Dimitrijević’s playwriting is lacking in optimism. It is rough and poetic, sometimes intentionally one-dimensional or anachronically refined, sometimes cheeky (like a child misbehaving) and ironic both towards the world and itself, but above all, it is dramatically exciting, rich in emotion, and in some segments, almost classically strong in its fatalism. In terms of its content, and similarly the author’s other plays, the focus in The Folk Play is on succulently formed female characters (which are otherwise a rarity in domestic theatre and film), criticism of the patriarchal society, presence of social, gender and sexual inequality, questioning of freedom and rebellion within the framework of melodramatic matrix (“social context defines characters’ destinies”), laughter, crying and constant rollicking with pop culture, which is a compulsory camp element (in the widest sense of the phenomenon). At first glance, one could say that the plot of The Folk Play is based on a strange love triangle: strange, because one of the sides is lacking love. Behind the picture portraying “two people who are in love and a third person who is in their way”, emerges a country, in which everything different is barely acceptable or totally unacceptable, and a mentality which allows only that with respect how things were done „since the dawn of time“. Then, of course, there are the issues of feminism and women’s emancipation and a corresponding critique when it turns out that patriarchal norms are deeply embedded in all these women (daughters, wives, mothers), who are trapped within the traditional framework. When portraying the place where play is set, the author presents a clear paradox: “This place is a village. And a hill. And a small river. At the outer edge of the village, there are many small white houses and a lot of grass, on which cows can happily graze. (…) This is, maybe, the case only in summer. The rest of the year, there is mud all over the place and the little river is littered with garbage.” The relationship which takes place in this environment, between a certain Anka (who is “not made for this world”) and the folk singer Branka (who roams the world, wishing never to visit the same place twice), doesn’t exist so as to make sexuality the main topic. The theme is dramaturgically obvious and its purpose is to overcome various stereotypes and remove social distance between the two characters. The dominant trait, which surpasses sexuality and which can be observed in all the characters, is their manner of facing problems, or rather their sweeping of problems “under the carpet”. It is much easier to pretend not to see the elephant in the room. It is like when we pretend to despise a political party, but the same party wins with a large majority of votes at the elections. It is like when we loathe folk music, but the concert halls are filled to capacity for each folk concert, while theatres could only dream of such numerous audiences. The folk songs of The Folk Play, which are integral to it, all date back to the late 1980s, but their purpose is not to evoke nostalgia for the time before of desintegration of Yugoslavia.

Maybe, these folk songs only announced what would come later on. They represent a reminder of the fragile period when the motto “we are all middle class” slowly, but surely, became inaccurate. In one of her interviews, the playwright said, “I firmly believe that folk music contains a certain subversive potential, which we should not renounce easily. As much as it seems to support certain dominant values, which we would label as negative, at the same time, it rebels against such values with the same intensity. (…) Of course, when something has been socially unacceptable for so long, in cultural, urban and intellectual circles, to which you nominally belong, you start wondering what is wrong with you, and then, you start wondering what provokes so much hatred and an a priori rejection of popular culture’s complex product. And then, you see how the elite falls easily into a trap, because it incessantly considers folk music through misogynistic and class formulation (‘bare-ass singer’, ‘only the village folk listen to that music’, etc.). Very often, in this non-critical approach, which certain elite circles adopt when folk music is concerned, we can easily distinguish loathing towards ‘the masses’.”

In The Folk Play, the lyrics of folk songs speak about love. About sadness and sobering. About passion and suffering. About determination and vulnerability. About the mud we swim in and our wish to escape. Unfortunately, they are also about the fact that we most often satisfy ourselves with shortcuts: instead of getting rid of the mud, we only change the style of swimming. Just like Anka seems to threaten to “derail, suddenly and unexpectedly…”, while everything she does actually denies that. Her fears paralyse her; they make her incapable of suffering for somebody else, and of sincerely perceiving somebody else’s emotions. She is her own worst enemy. On the other hand, Branka accepts herself. She is honest even when she lies and when she speaks the truth, and when she speaks the so-called truth. After all, she is on first name basis with the tavern. The two women’s escape to freedom will be short lived. However, at the moment of their escape, they will both feel truly alive. Everything else is “hello, goodbye, farewell…”

Slobodan Obradović

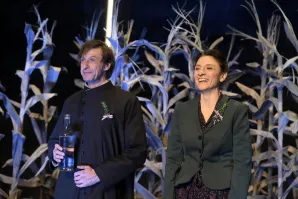

Olga Dimitrijević

Olga Dimitrijević

Olga Dimitrijević, born in 1984, has graduated from the Department of Dramaturgy at the Faculty of Drama Arts in Belgrade. She wrote theatre reviews for the Vreme and the Teatron magazines. Produced plays: The Boarding School (Dadov, 2009), Workers Die Singing (Heartefact Fund and Bitef, 2001), The Folk Play (Bora Stankovic Theatre, Vranje, 2012) and Stop to Say Hello within The Craving Flow Project (Tkh, CDU, Zagreb, 2014). Other projects include: cabaret Behind the Mirror (Rex Cultural Centre, 2012), co-editing of the book Among Us – Untold Stories of Gay and Lesbian Lives (Heartefact Fund, 2014), stage directing and dramatization of a novel Red Love by Alexandra Kollontai (Bitef Theatre, 2016), intermittent lecturing at the Women’s Studies Centre in Belgrade, dramaturgical work in theatre. Olga won the following awards: Heartefact Fund Award, Sterija’s Award and Mihiz Award for playwriting. Often, she dreams of revolution.

BOJANA LAZIĆ

BOJANA LAZIĆ

Bojana Lazić was born in Belgrade in 1977. Bojana is a stage director who staged over 20 theatre productions in both well-established and unestablished theatres; she won several theatre awards.

Productions

Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett, Yugoslav Drama Theatre

Roberto Zucco by B. M. Koltes, National Theatre Kikinda

Sex, Lies and Wild Geese by Woody Allen, National Theatre Subotica

Twelfth Night by William Shakespeare, “Boško Buha” Theatre

Pippi Longstocking by Minja Bogavac after A.Lindgren’s book, “Boško Buha” Theatre

Pay Attention by Milan Marković, “Boško Buha” Theatre

The Bereaved Family by Branislav Nušić, Šabac Theatre

Half and Half by Minja Bogavac, Little Theatre “Duško Radović”

Hen by Nikolay Kolada, National Theatre “Toša Jovanović”, Zrenjanin

Katzelmacher by Rainer Werner Fassbinder, National Theatre Pirot

The Just Assassins by Albert Camus, National Theatre of Republika Srpska, Banja Luka

Fahrenheit 451, based on Ray Bradbury’s novel, National Theatre Niš

INTERVIEW WITH THE DIRECTOR

The Folk Play is a play about freedom and love

What’s the starting point for your staging of the play, where one of the central themes is the love between two women?The Folk Play is a play about love between two women, which means that two universal themes, extremely important in the XXI century – the theme of freedom and the theme of love, are deeply set in the play, as well as the issues of freedom in love and, possibly, love in/at freedom. Olga Dimitrijević set the play in a village, which means that the play considers the ideas of the Serbian family as well relationships within a patriarchal context. In its form and language, The Folk Play is a mixture of realistic dialogues and massive, poetic, almost classical textual torrents. The play’s heroines, Anka and Branka, have the power to stay within the play, but also the power to exit the play in order to communicate with the audience. The text is sometimes spoken in prose and sometimes in verse, and everything is interwoven with folk songs’ lyrics. It’s very potent material for the whole cast and team, which is very important in theatre. It’s very important to find joyfulness in the text!

The Folk Play, among other things, deals with issues of authoritarianism and inequality; those issues are being spoken about quite frequently today. Can an individual who lives in an extremely patriarchal and conservative environment, as is the case in the play, change the world around themselves? himself/herself?

I would love to believe that they could; however, unfortunately, I think that they cannot. It is important to try, though. You see, maybe the effort cannot change the world, but it changes the person who tries to change the unchangeable world. Our heroine, Anka, does not succeed in changing her parents’ views, but, in a strange way, she manages to get a hold of her life and to mature. In the play, we deal with three generations of women and their respective aspirations regarding love and freedom. Every evening, Anka’s mother watches the Moon and ‘dreams’ for hours, but she has never tried to leave her own backyard. On the other hand, Branka decides to leave her village forever and never, never, return. On her way to a big city, she meets young Anka, for whom everybody says that she is not made for this world. Anka has the same desire as her mother, and now she finds herself tempted to do something that she has longed to do all her life – to fight for herself.

Regarding its genre, the play is a socially engaged musical, which is, as you said, interwoven with folk songs’ lyrics. What makes this kind of music suitable to portray such a sensitive social topic?

In terms of the genre, I would not say that it is a musical, but rather a musical performance, which uses music as the language of love. The ‘Soundtrack’ is interwoven into the plot, it features songs by Šemsa Suljaković, Ljuba Aličić, Mira Kosovka, Gordana Stojićević, Hasan Dudić, Ana Bekuta, etc. I still remember all the folk songs I heard as a child; they would play from my grandfather’s radio, which hung on a nail on the old house’s façade. This sort of music comes from the people and belongs to the people; thus, it belongs to the social background in which the plot takes place.

As a director, you like to provoke audiences with your productions. Which issues will touch the viewers? What will make them contemplate?

While working on this play, I have found that the emotion is important, not the provocation. The fact that The Folk Play is being produced in the National Theatre is provocative enough for the conservative part of the public. As a director, I am interested in creative exchange and opening of a wider field of freedom for every author. I have had the opportunity to work with amazing actors who invest a lot of intelligence and thought into their roles. They are the ones who will touch us with their emotions. It’s something that would certainly touch the viewers.

Mikojan Bezbradica, The Theatre Magazine, no. 99, September 2016

Premiere performance

Premiere november 17, 2016. / "Raša Plaović" Stage

Stage Director Bojana Lazić

Text Adaptation Bojana Lazić, Slobodan Obradović

Dramaturgy Slobodan Obradović, Molina Udovički Fotez

Set Designer Zorana Petrov

Costume Designer Marina Vukasović Medenica

Composer Vladimir Pejković

Stage Movement Damjan Kecojević

Speech Dijana Marojević

Executive Producer Milorad Jovanović

Producer of the performance and Assistant Director Natalija Ignjić

Premiere Cast:

Anka Ana Mandić

Branka Sena Đorović

Milan Ivan Marković

Jelica Anastasia Mandić

Dragan Slobodan Beštić

Savka Nela Mihailović

Zoran Aleksandar Đurica

Anka's Bees in Bonnet NIna Nešković, Milica Sužnjević, Mina Obradović

Stage Manager Aleksandra Rokvić

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Costume Design Assistant Olga Mrđenović

Set Design Assistant Jasna Saramandić

Light Operator Master Srđan Mićević

Make-up Dragoljub Jeremić

Set Crew Chief Zoran Mirić

Sound Operator Dejan Dražić

Video Technician Dejan Ostojić

Set and Costumes have been made in the National Theatre's Workshops