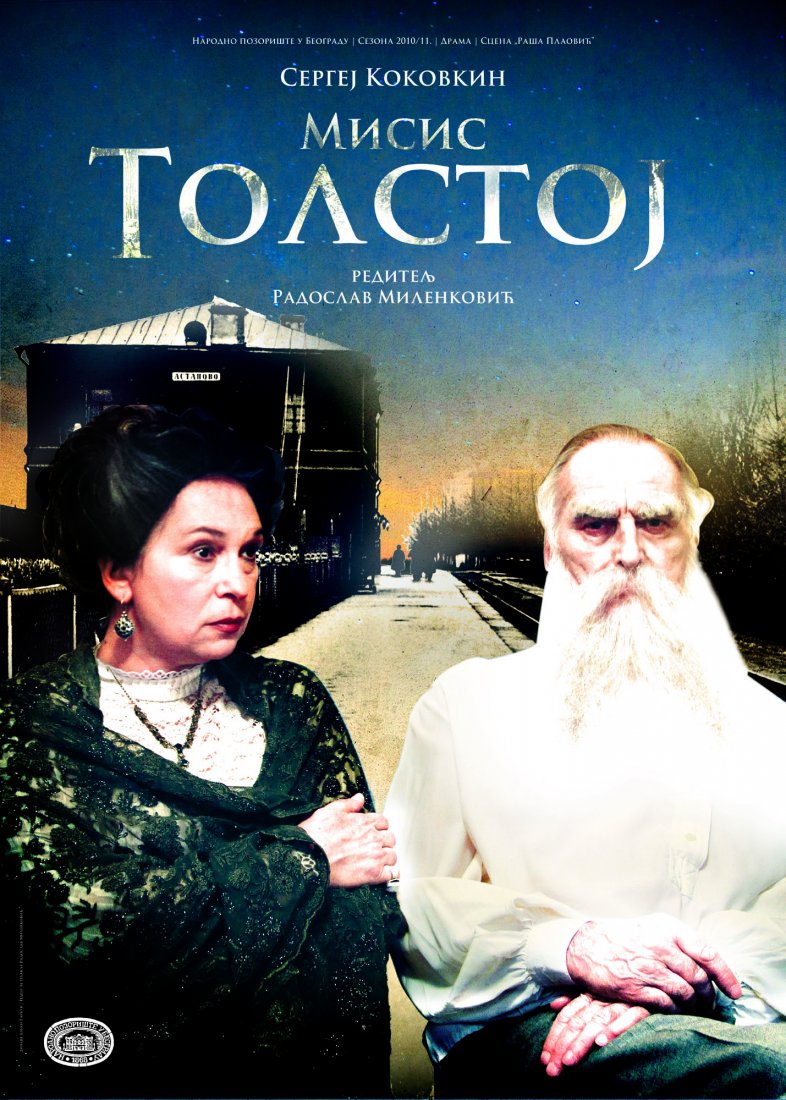

Mrs. Tolstoy

drama by Sergei Kokovkin

THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF COUNTESS SOPHIE TOLSTOI

TRANSLATORS’ NOTE

(...) The whole question of the will and the going away of Tolstoi, of the difference with his wife, and of the subsequent dealings with his property, has given rise to an immense literature-in Russia. As Spiridonov’s preface shows, it is treated as a trial in which the whole of humanity is to judge between Tolstoi and his wife. The importance of this book lies in the fact that in it Countess Sophie Andreevna Tolstoi herself states her own case in full. (...)

PREFACE By Vasilii Spiridonov

(...) The history of the manuscript is as follows: - At the end of July, 1913, S. A. Vengerov sent a letter to S. A. Tolstoi asking her to write and send him her autobiography, which he proposed to publish. (...) All this creates an impression in the reader’s mind that S. A. T., in writing her autobiography, was guided by a definite purpose, to contradict the unfavourable rumours about her which circulated everywhere and were getting into newspapers and magazines. (...) In another place, in her preface to Leo N. Tolstoi’s Letters to His Wife, published in 1918, she says frankly: “This, too, has induced me to publish these letters, because, after my death which in all likelihood is near, people will, as usual, wrongly judge and describe my relations to my husband and his to me. Then let them study and form their judgment upon living and genuine data, and not upon guesses, gossip, and inventions.

We shall understand S. A. T.’s desire, if we consider her position. It is true that the great honour of being the wife of a genius fell to the lot of S. A. T., but there also fell to her lot the difficult task of creating favourable conditions for the life and development of that genius. She knew the joy of living with a genius, but she also knew the horror of living in public, when her every movement, smile, frown, incautious word was in every one’s eyes and ears (…) Forty-eight years is a long road. Many unnecessary words were spoken in that time, many incautious move¬ments made.(…) And for everything she will be made to answer before the court of mankind. S. A. T. knew this, and with an anxious heart she prepared herself for the judgment. The Auto-biography and L. N. Tolstoi’s Letters to his Wife are the last words of the accused. (...) If S. A. T. bears a responsibility before all mankind, each of us before our conscience has a responsibility for whatever verdict we may pass upon her. (...)

A SHORT AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF COUNTESS SOPHIE ANDREEVNA TOLSTOI

(...) When children began to appear upon the scene, I could no longer devote myself entirely to my husband’s service and to the constant sympathy with his work. We had many children; I bore thirteen. Ten of them I nursed myself, on principle and because I wanted to do so. I did not want to have wet-nurses. Owing to diffi¬culties, I had to give up the principle on three occasions.

(...) 1881 when we moved to Moscow for the winter. Our eldest son, Serge entered the university; our two other sons, Ilya and Leo, were sent by Leo Nikolaevich to L. I. Polivanov’s classical school. He sent our daughter, Tanya, to the School of Painting and Sculpture, and he took her out to her first fancy-dress ball at the Olsufevs, as I was expecting my eighth child, Alesha, born on October 31., and did not go out anywhere.

(...) The difference between my husband and myself came about, not because I in my heart went away from him. I and my life remained the same as before. It was he who went away, not in his everyday life, but in his writings and his teachings as to how people should live. I felt myself unable to follow his teaching myself. But our personal relations were unaltered: we loved each other just as much, we found it just as difficult to be parted even temporarily (...) Only rarely was our happiness clouded and the harmony broken by flashes of mutual jealousy, which had no ground at all. We were both hot-tempered and passionate; we could not bear the thought that any one should alienate us. It was just this jealousy which woke up in me with terrible force when, towards the end of our life, I realized that my husband’s soul, which had been open to me for so many years, had suddenly been closed to me irrevocably and without cause, while it was opened to an outsider, a stranger. (...) In four years we had suffered five losses in the family. (...) three of our young children died.

(...) Whether these events influenced Leo Nikolaevich or whether there were other causes, his discontent with life and his seeking for truth became acute. (...) A spirit which rejected the existing religions, progress, science, art, family, everything which mankind had evolved in centuries, had been growing stronger and stronger in Leo Nikolaevich, and he was becoming gloomier and gloomier. (...) I was alarmed, frightened, grieved. But with nine children I could not, like a weather-cock, turn in the everchanging direction of my husband’s spritual going away. (...) When exactly we parted from him and over what, I do not know, I cannot remember. (...) I simply could not understand why should I change my life. (...) If I had given away all my fortune at my husband’s desire (I don’t know to whom), if I had been left in poverty with nine children, I should have had to work for the family – to feed, do the sewing for, wash, bring up my children without education. Leo Nikolaevich, by vocation and inclination, could have done nothing else but write.

(...) In the summer of 1884 Leo Nikolaevich worked a great deal on the land; for whole days he mowed with the peasants, and, when tired out he came home in the evenings, he used to sit gloomy and discontented with the life lived by the family. That life was in discordance with his teaching, and this tormented and pained him. At one time, he thought of taking a Russian peasant woman, a worker on the land, and of secretly going away with the peasants to start a new life; he confessed this to me himself. At last, on June 17, after a little quarrel with me about the horses, he took a sack with a few things on his shoulder and left the house, saying that he was going away for ever, perhaps to America, and that he would never come back. At the time I was beginning to feel the pains of child-birth. My husband’s behaviour drove me to despair, and the two pains, of the body and of the heart, were un¬endurable. I prayed to God for death. At four o’clock in the morning, Leo Nikolaevich came back, and, without coming to me, lay down on the couch downstairs in his study. In spite of my cruel pains I ran down to him; he was gloomy and said nothing to me. At seven o’clock that morning our daughter Alexandra was born. I could never forget that terrible, bright June night.

(...) In 1895 our youngest son, Vanichka, died. (...) My depression and loss of interest in everything continued during the summer, and it was only by chance and quite unexpectedly that my state of mind was changed – by music. That summer there was staying with us a well-known composer and superb pianist (*Sergei Ivanovich Taneev /1856-1915/ spent summers at their house in period 1894-95). (...)

In 1906, our daughter Masha died of pneumonia. (…) And how insignificant human vanity appeared to me! I seemed to be asking myself: what, then, is important? One thing; if God has sent us on to the earth and we are to live, then the most important thing is to help one another in whatever way possible. To help one another to live. I think the same now.

(...) Even before this, the influence of outside people was creeping in and towards the end of Leo Nikolaevich’s life it assumed terrifying dimen¬sions. For instance, these outsiders frightened Leo Nikolaevich that the Russian Government would send the police and seize all his papers. On that pretext they were removed from Yasnaya Polyana, and, therefore, Leo Nikolaevich could no longer work at them, as he had not the whole material. Eventually with difficulty, I succeeded in getting back seven thick notebooks containing my husband’s diaries, which are now in the possession of our daughter Alexandra; but the affair led to strained relations with the man who had them in his keeping, and he ceased his daily visits (*Chertkov).

(...) Owing to these agitations and to the difficulty and responsible work connected with L.N.Tolstoi’s publications, I continually grew more nervous and worried, and my health broke down completely. I lost my mental balance, and, owing to this, I had a bad effect upon my husband. At the same time Leo Nikolaevich began con¬tinually to threaten to leave the house, and his “intimate” friend (*Chertkov) carefully prepared, together with the lawyer M., a new and correct will, which was copied by Leo Nikolaevich himself on the stump of a tree in the forest on July 23, 1910. This was the will which was proved after his death.

(…) In his diary he wrote at the time, among other things: “I very clearly see my mistake; I ought to have called together all my heirs and told them my intention; I ought not to have kept it. (...)“

(…) Almost daily I visit the grave; I thank God for the happiness granted to me in early life, and as to the last troubles between us I look upon them as a trial and a redemption of sin before death. Thy will be done.

COUNTESS SOPHIE TOLSTOI.

OCTOBER 28, 1913,

YASNAYA POLYANA.

From: The Autobiography of Countess Sophie Tolstoi

With preface and notes by Vasilii Spiridonov

Translated by S.S.Kotelianski and Leonard Woolf

Published at the Hogarth press, Paradise road, Richmond, 1922

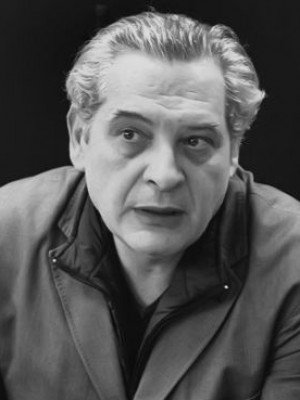

SERGEI KOKOVKIN

SERGEI KOKOVKIN

Playwright, director, screenwriter, actor, author of thirty plays that have been translated in twelve languages, and have been staged widely in Russia and abroad. He graduated from Nakhimov Navy School, the Institute of Theater, Arts, Music and Cinematography (modern Theater Academy of Saint-Petersburg), class-drama and work in Petersburg and Moscow theaters. His cinema work includes acting, direction and screenwriting. He has staged plays in a variety of countries and for the last few years has been teaching in United States of America. Sergei is an artistic director of All Russian playwrights conference, is a member of the Writers Union, the author of the books “Come to me”, “Five Corners”, “Missis Leo and others” and “The Simpleton”. He has been awarded an “American award of Fine Arts” and Honored Artist of Russia.

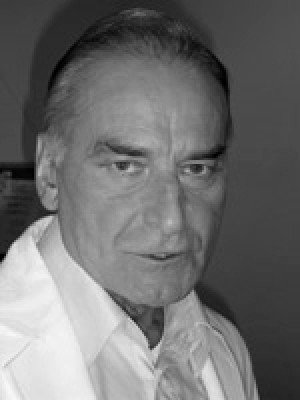

RADOSLAV MILENKOVIĆ

RADOSLAV MILENKOVIĆ

Radoslav Milenković was born in Novi Sad on 17 February 1958. He graduated from the Acting Department at the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad, the class of Professor Branko Pleša in 1980; and in 1990, he graduated from the Department of Theatre and Radio Directing at the Faculty of Dramatic Arts in Belgrade, the class of Professor Dejan Mijač. He also attended the Ladislav Fialka’s Summer Course of Pantomime (Dubrovnik, 1978) and the Jacques Lecoq’s Summer School of Stage Movements (Paris, 1979). In the course of his prolific career, Milenković was one of founders of the MM Theatre in Zagreb; he acted in the Theatre &TD in Zagreb (1984–87), Yugoslav Drama Theatre in Belgrade (1987–2005); he taught acting and speech at the Academy of Arts in Novi Sad (1989–93); he was a Drama Company manager in the Serbian National Theatre in Novi Sad (1995–96), where since 2005, he has been permanently engaged as a director. In addition, he was an artistic consultant in the National Theatre “Toša Jovanović” in Zrenjanin in 2006 and 2007; and since 2010, he has been an artistic consultant at the Cultural Institution “Vuk Karadžić”. Milenković is a guest director at Csiki Gergelyi színház in Kaposvar, Gardonyi Géza színház in Eger and Miskolci nemzeti színház. He has played more than 50 roles in the most prominent theatres in Belgrade, Novi Sad and Zagreb, as well as at the Dubrovnik Summer Festival, out of which his most outstanding ones have been in plays dramatized after national writers’ pieces (J. S. Popović, G. Stefanovski, A. Popović, D. Kovačević, Lj. Simović, S. Kovačević, S. Selenić, D. Ćosić, B. Pekić). He has also played numerous roles in TV dramas and films directed by the most prominent national directors (Zdravko Šotra, Emir Kusturica, Srđan Dragojević, Oleg Novković, Srđan Koljević, etc.), as well as by internationally renowned directors (Ferdinando Orgnani, Alberto Sironi, Lamberto Bava, Ralph Fiennes). He has directed plays by Mrozek, Kohout, Weiss, Schisgal, Beckett, Roger Vitrac, Jari, Strindberg, Ostrovski, Gorky, Kolyada, Razumovska, Petruševska, von Horvath, McDonough, Kretzu, Nabokov, Sartre, Camus, Ionesco, Moliere, Shafer, Voltaire, Chekhov, Bulgakov, Lorca, Shakespeare, Držić, Popović, Stefanovski, Romčević, Krečković, Domanović, Bećković, etc. in theatres across Serbia, Hungary, Sweden, Croatia and Macedonia. Milenković has received numerous awards for acting and directing in many festivals in Yugoslavia and Serbia. In his career, he has dramatized pieces by Bećković, Domanović, Sremac, Kočić, Ranko Marinković, Greene, Kafka, Kolody, Bulgakov for theatre and radio productions. He is the son of Ljuba and Đorđe. He is the father of Natalija and Arsenije. He lives in Belgrade.

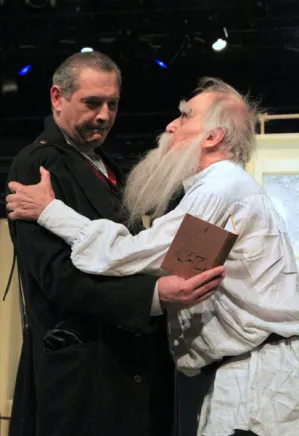

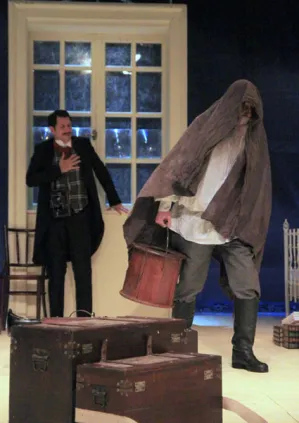

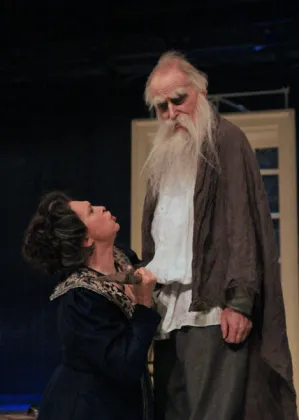

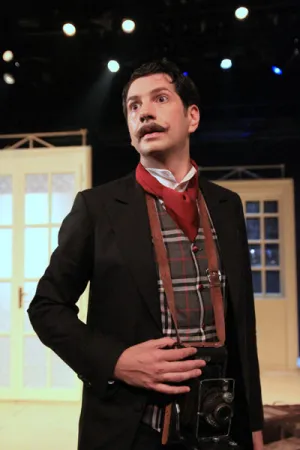

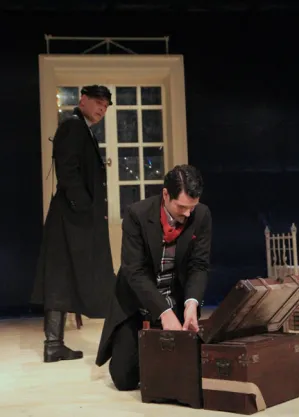

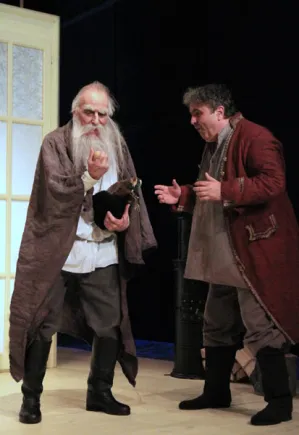

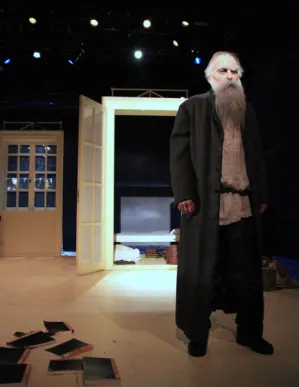

Premiere performance

Premiere 4 June 2011 / “Raša Plaovic“ Stage

Translated by Novica Antić

Director Radoslav Milenković

Dramaturge Ivana Dimić

Set Designer Boris Maksimović

Costume Designer Olga Mrđenović

Sound Design Marko Fabri

Scenic Speech Lјilјana Mrkić Popović, PhD

Music Selection Radoslav Milenković

Premiere Cast:

Count Tanasije Uzunović

Countess Nada Blam

Jermil Dragan Nikolić

Chertkov Nebojša Kundačina

Tanya Bojana Stefanović

Tapsell Mihailo Lađevac

Cherkez Pavle Jerinić

Producer Nemanja Konstantinović

Stage Manager Đorđe Jovanović

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Chicken created by Janka Haraszt

Assistant Costume Designer Marija Tavčar

Light Operator Srđan Mićević

Make-up Dragoljub Jeremić

Set crew Chief Nevenko Radinović

Sound Operator Dejan Dražić

Set and costumes were manufactured in the workshops of the National theatre in Belgrade

Translated by Novica Antić

Director Radoslav Milenković

Dramaturge Ivana Dimić

Set Designer Boris Maksimović

Costume Designer Olga Mrđenović

Sound Design Marko Fabri

Scenic Speech Lјilјana Mrkić Popović, PhD

Music Selection Radoslav Milenković

Cast:

Count Tanasije Uzunović

Countess Nada Blam

Jermil Dragan Nikolić

Chertkov Nebojša Kundačina

Tanya Bojana Stefanović

Tapsell Mihailo Lađevac

Cherkez Pavle Jerinić

Producer Nemanja Konstantinović

Stage Manager Đorđe Jovanović

Prompter Gordana Perovski

Chicken created by Janka Haraszt

Assistant Costume Designer Marija Tavčar

Light Operator Srđan Mićević

Make-up Dragoljub Jeremić

Set crew Chief Nevenko Radinović

Sound Operator Dejan Dražić

Set and costumes were manufactured in the workshops of the National theatre in Belgrade